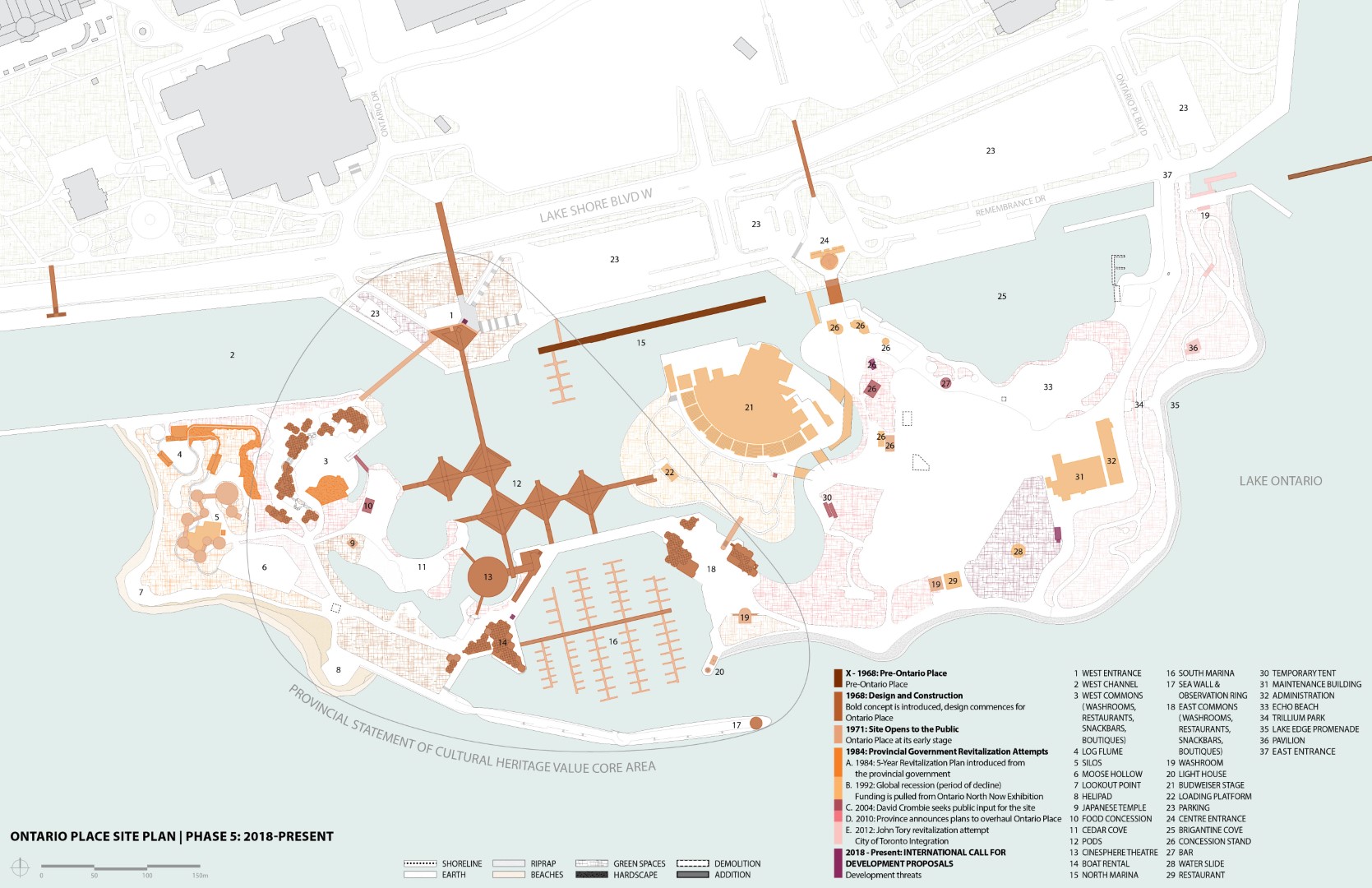

Explore the site

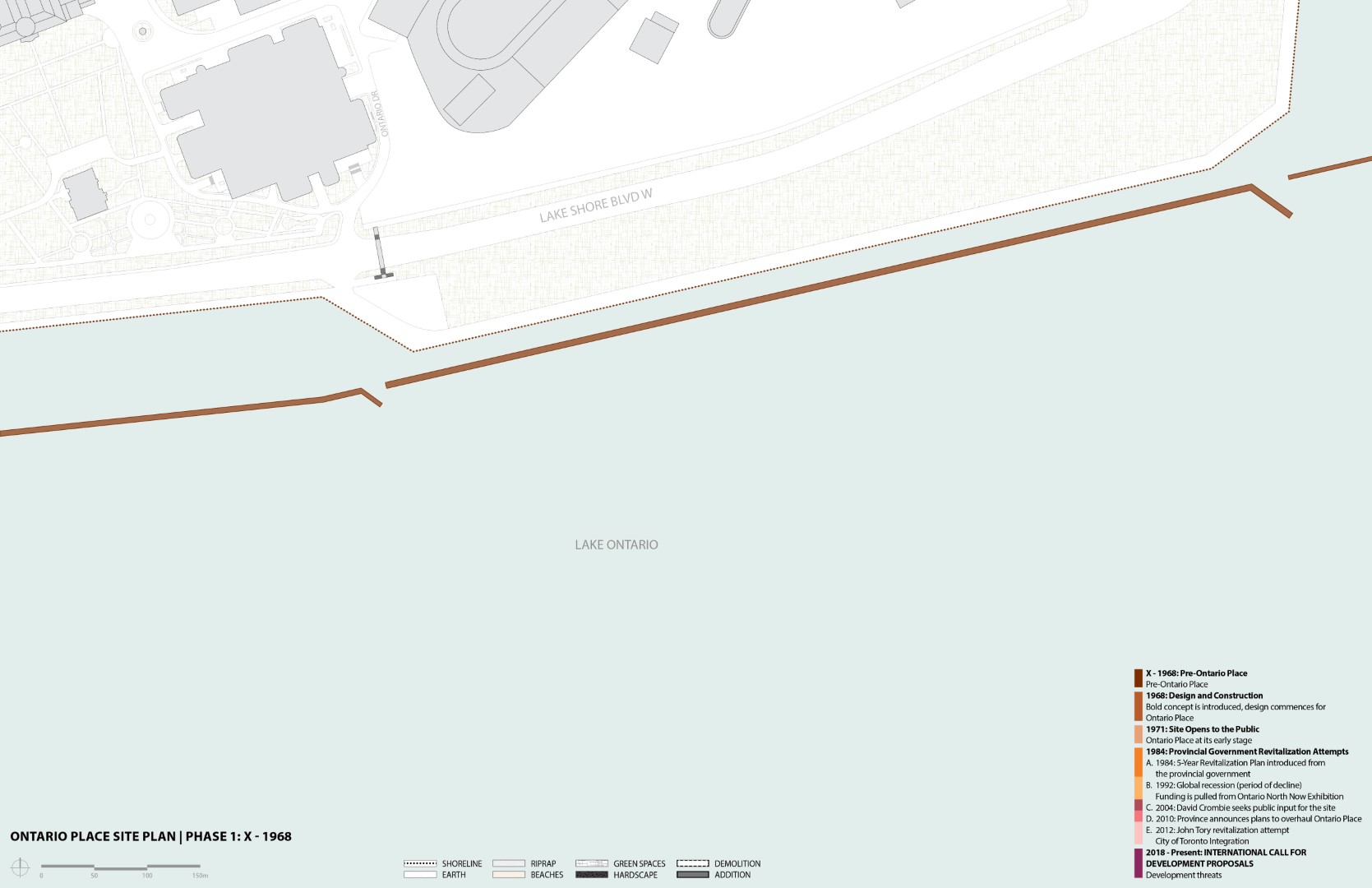

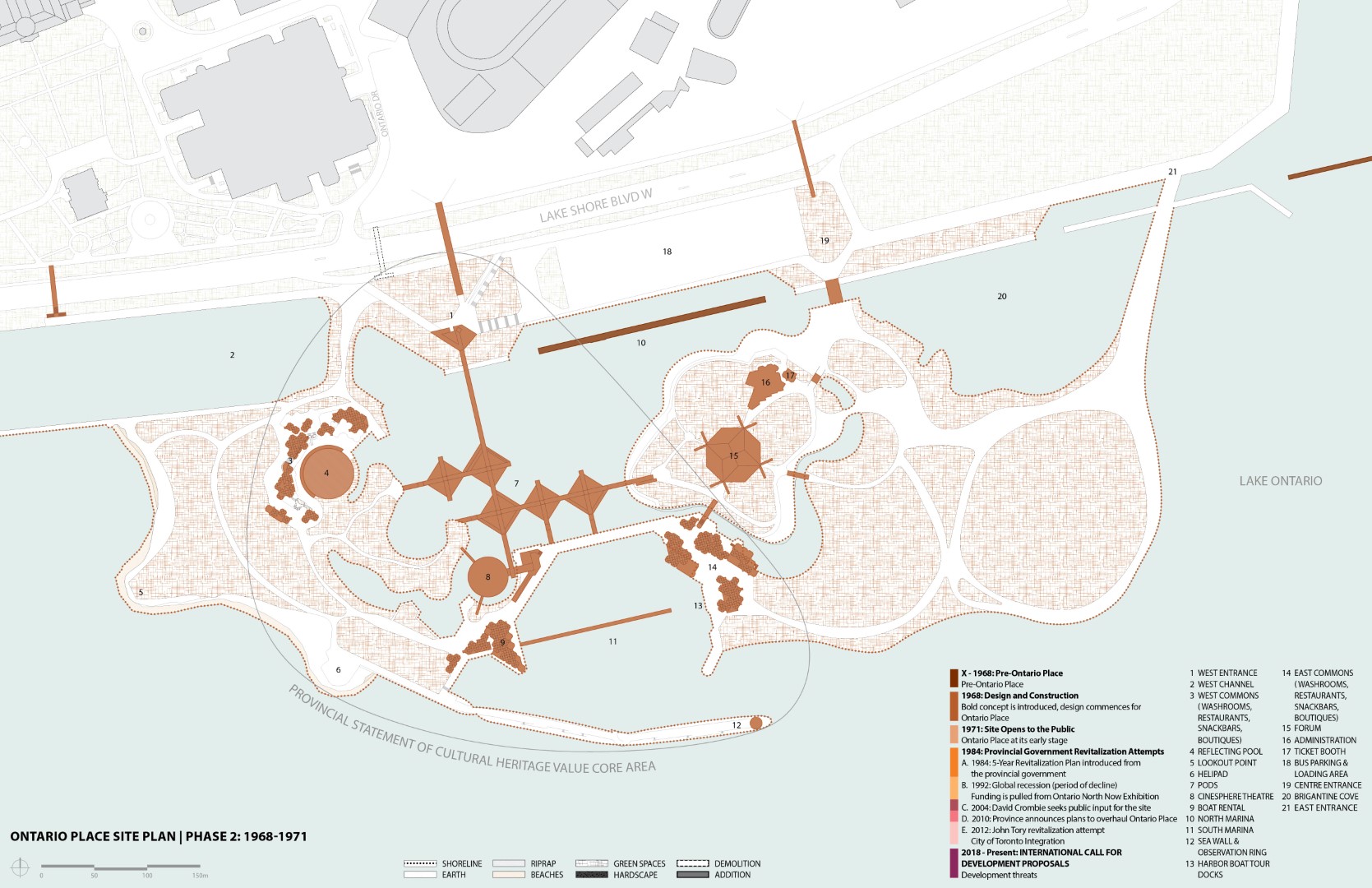

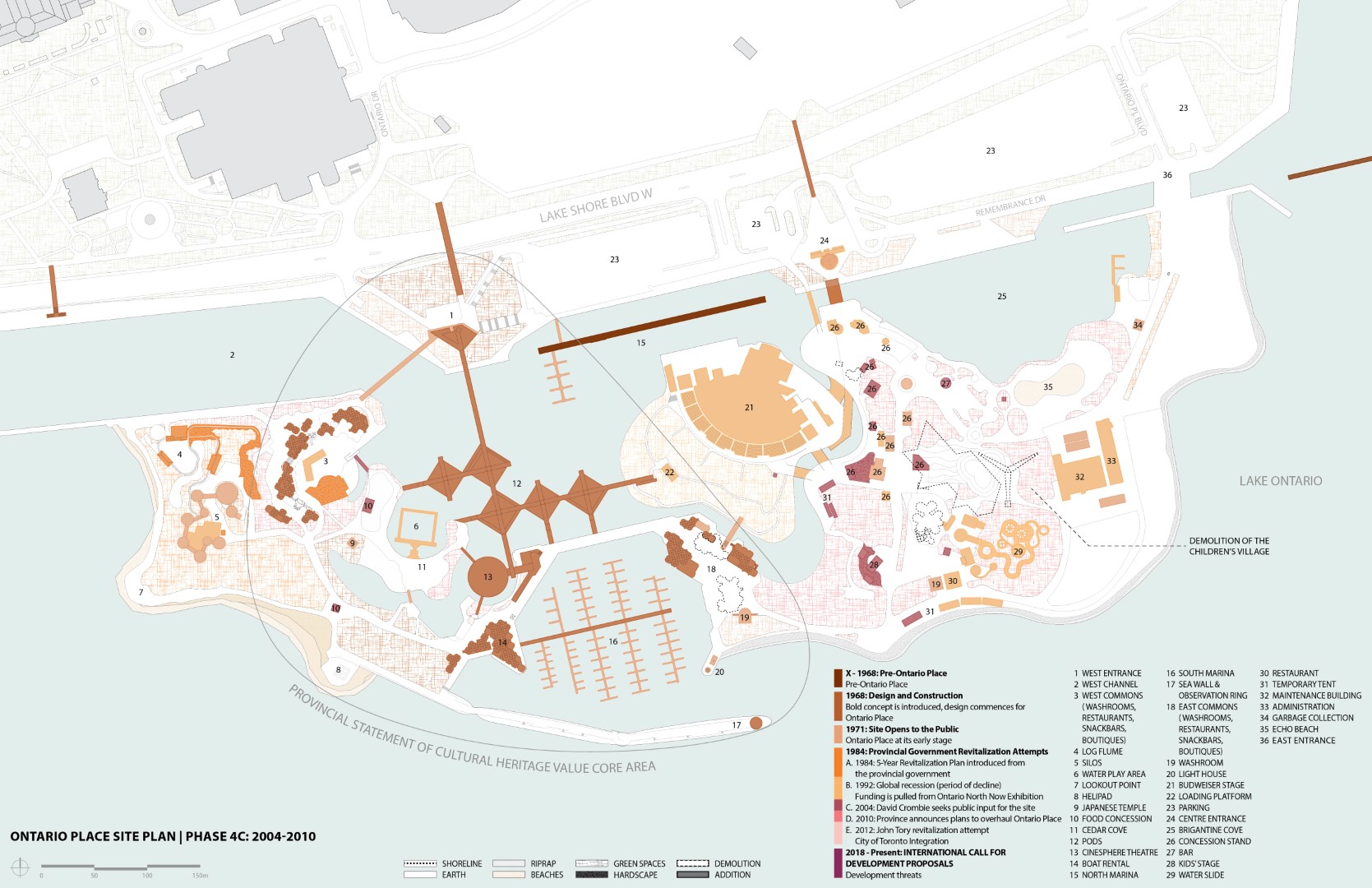

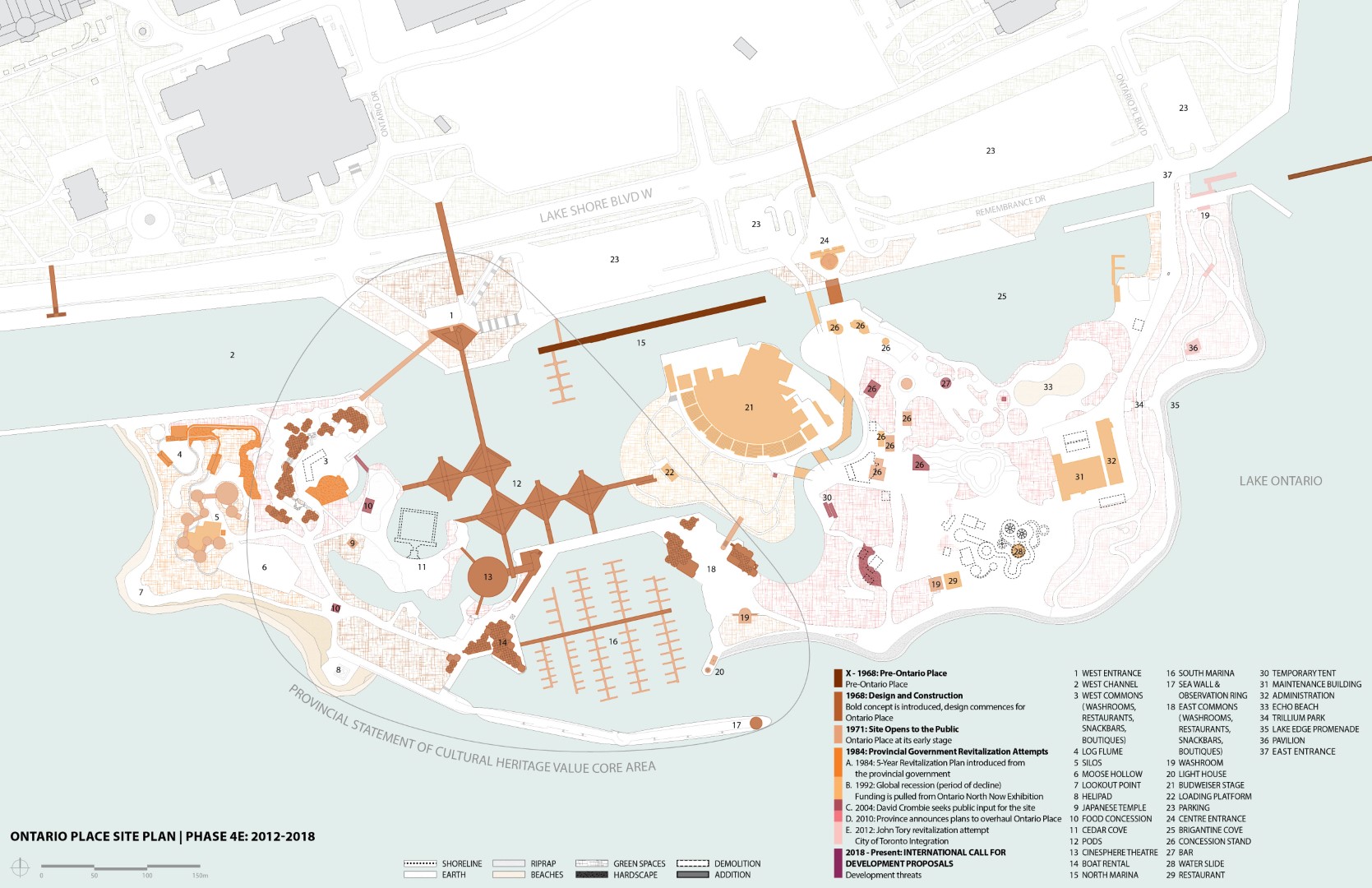

Student researchers from the University of Toronto have been working to track the complex and previously unrecorded histories of Ontario Place. The following sequence of site plans represents these ongoing research efforts, using key development periods to contextualize changes to the site. The provincial government once understood the value of Ontario Place as a cultural heritage site, before it removed the listing from its website.

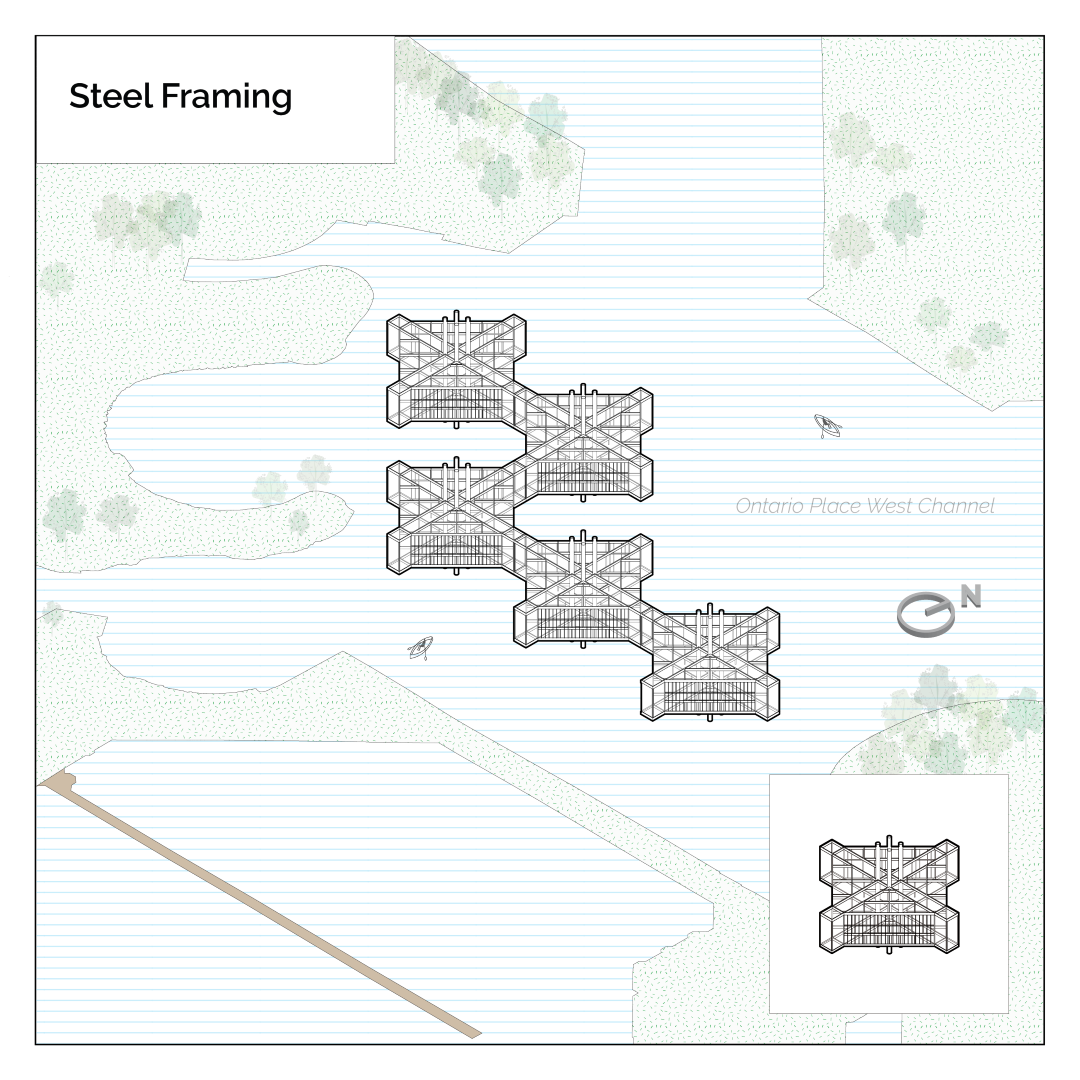

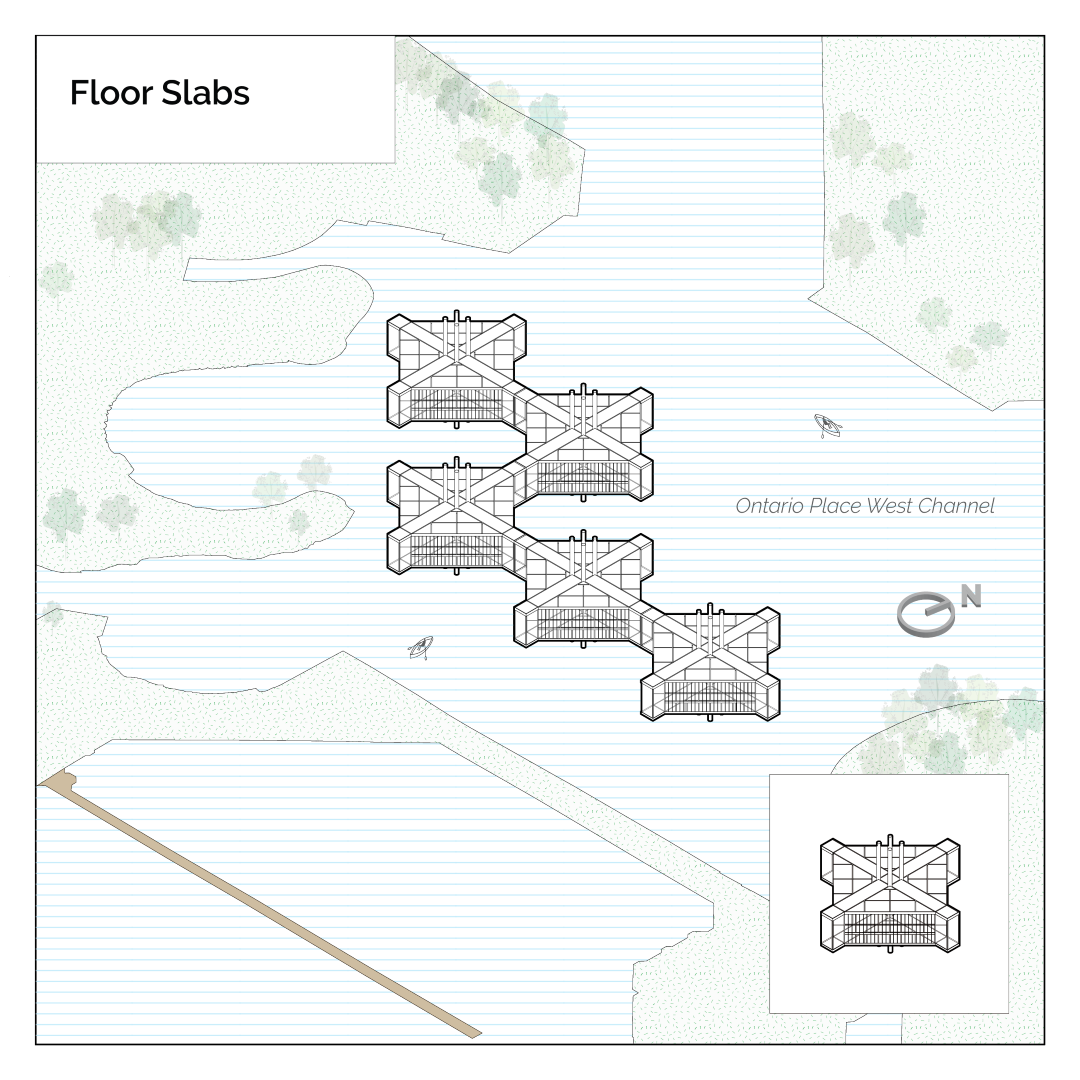

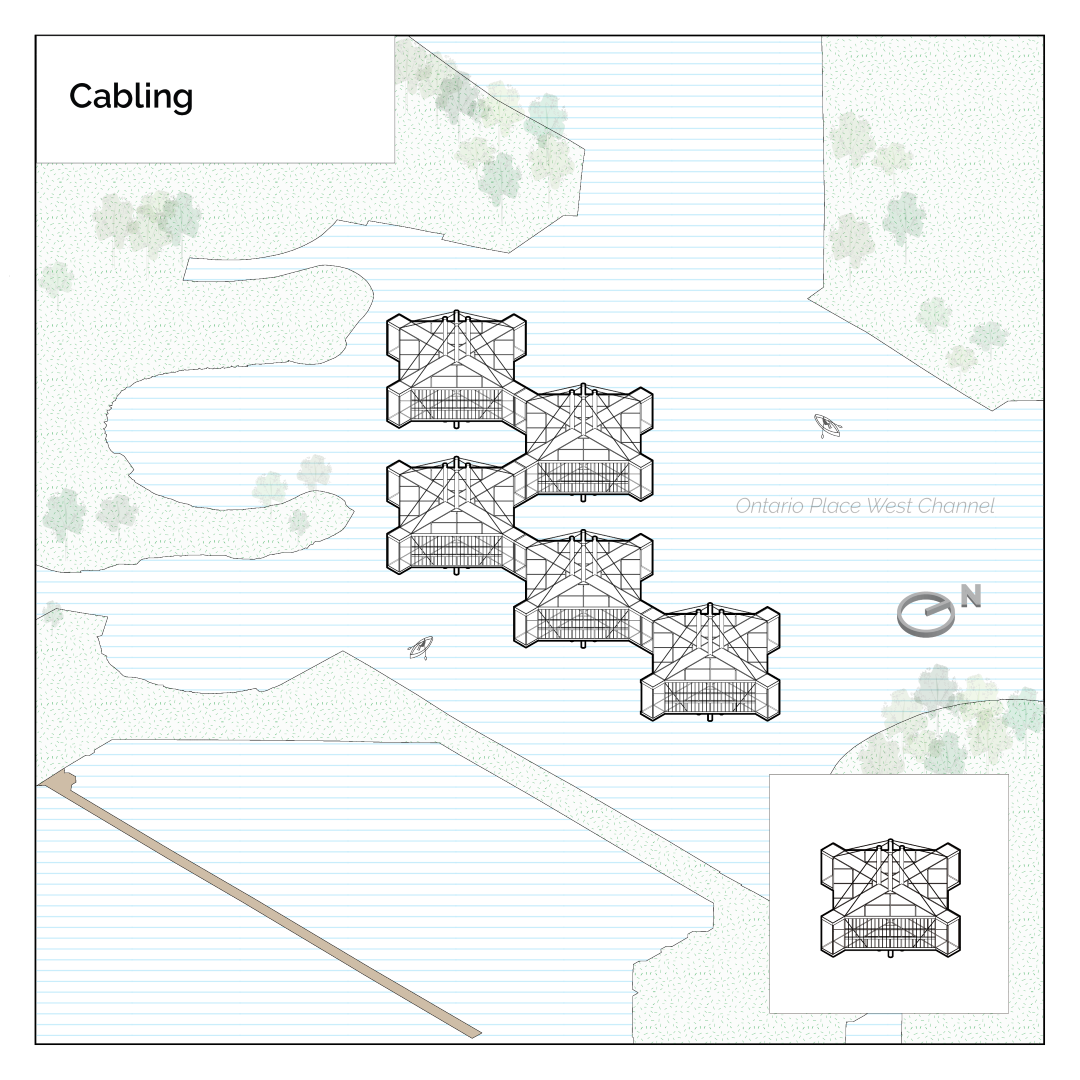

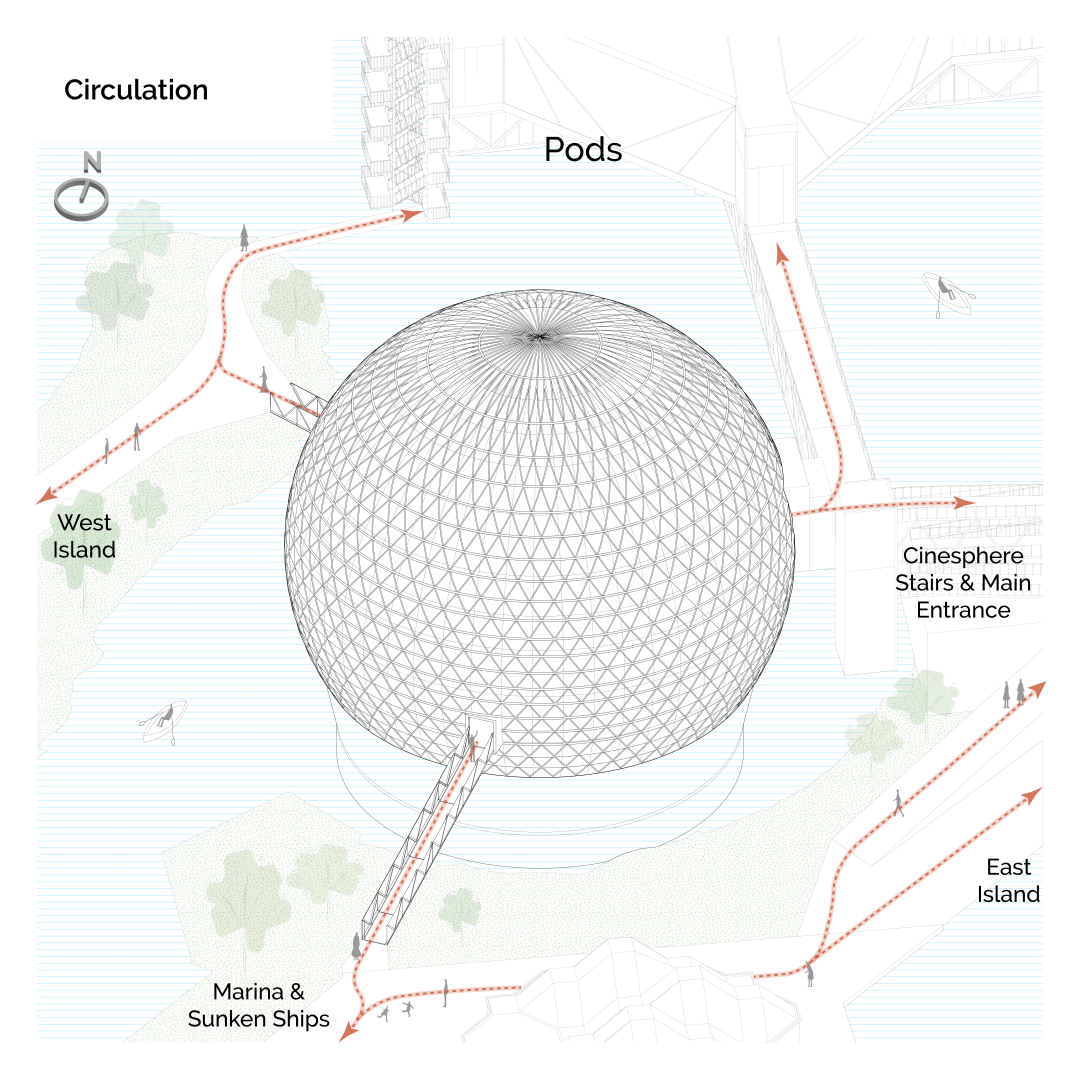

Pods

The Pods are five interconnected pavilions hung mast-like from cables. When Ontario Place opened in 1971, three pods housed exhibitions which explored Ontario’s past, present, and future-. The two remaining pods housed an entrance area and restaurant overlooking the artificial lagoon below. Architect Eberhard Zeidler has cited his inspiration for the Pods as oil drills, Crystal Palace, and the Eiffel Tower. The Pods also bear a striking resemblance to Archigram’s Plug-In University, only designed a few years prior to Ontario Place.

Eric McMillan (who later designed the Children’s Village) completed the original exhibition design in the Pods. Using moving walls, projections, and objects of various sizes, McMillan’s design required that visitors physically push their way through the space in order to navigate various exhibition compartments. In the mid 1990’s, the Pods hosted a Nintendo Power Pod, laser show, and various other attractions for children and youth. For most of their existence, the Pods have hosted various restaurants, often used by members of the Provincial Government to entertain guests. One of the Pods accommodates a rooftop deck, which has been used for various events through the years. The Pods remain closed, and require rehabilitation.

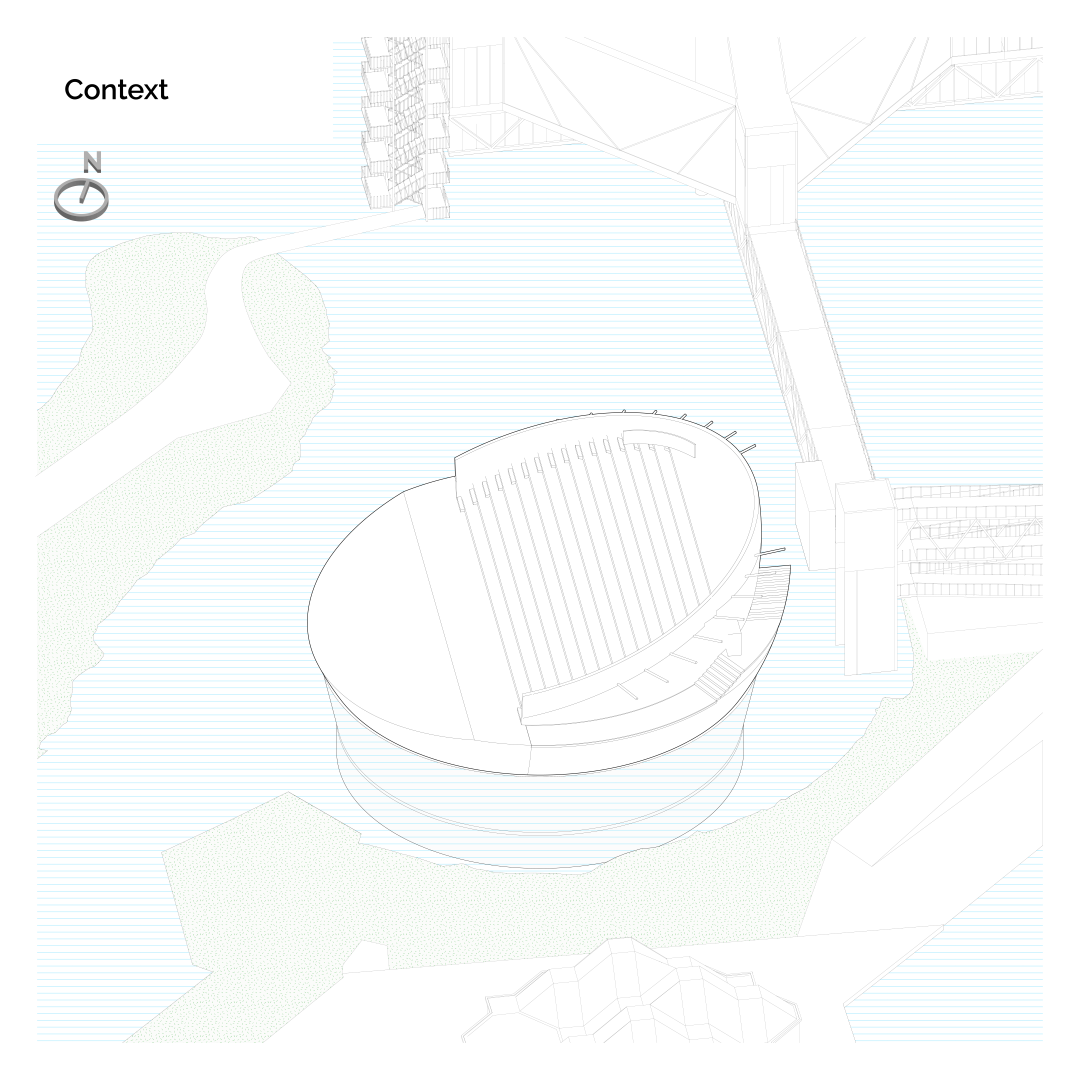

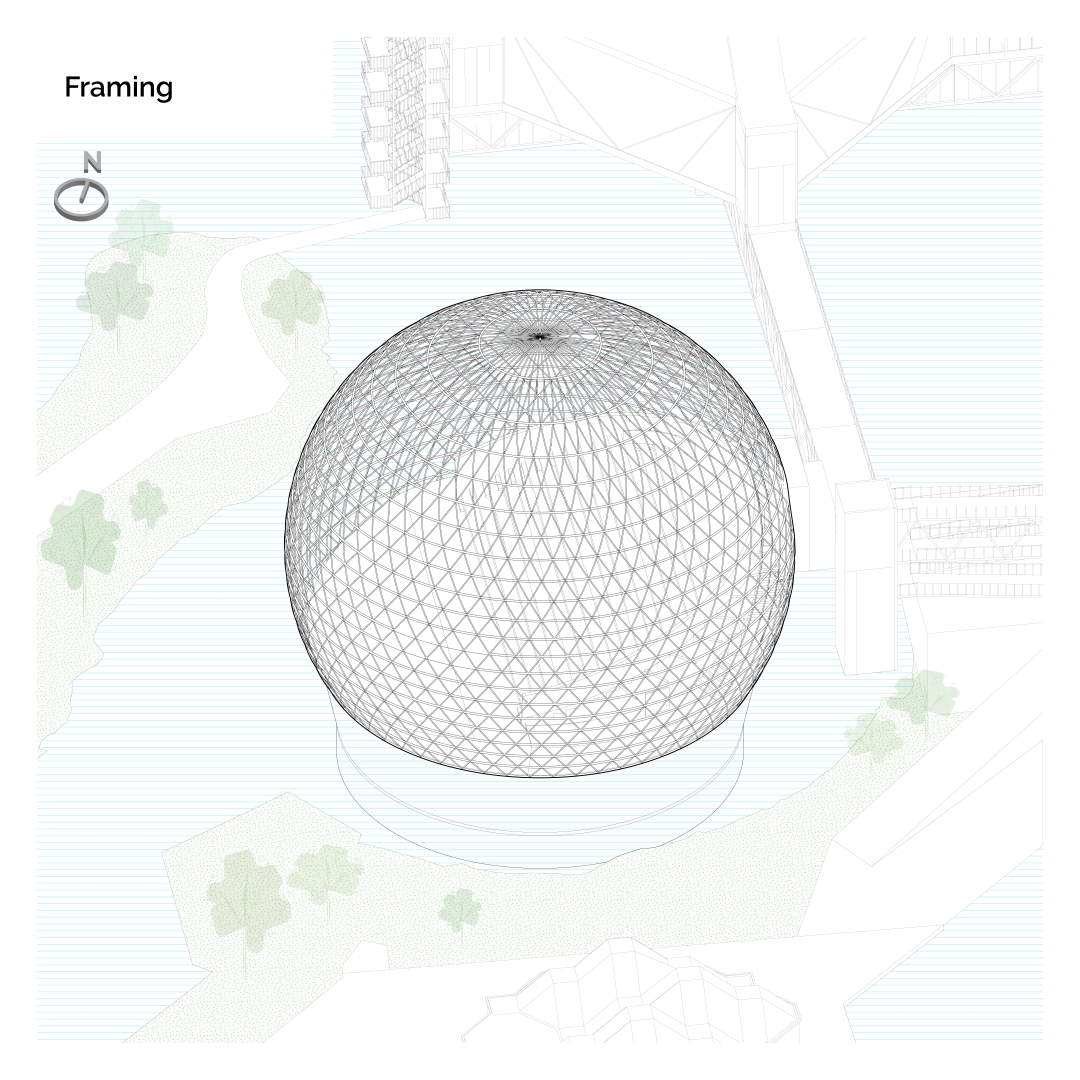

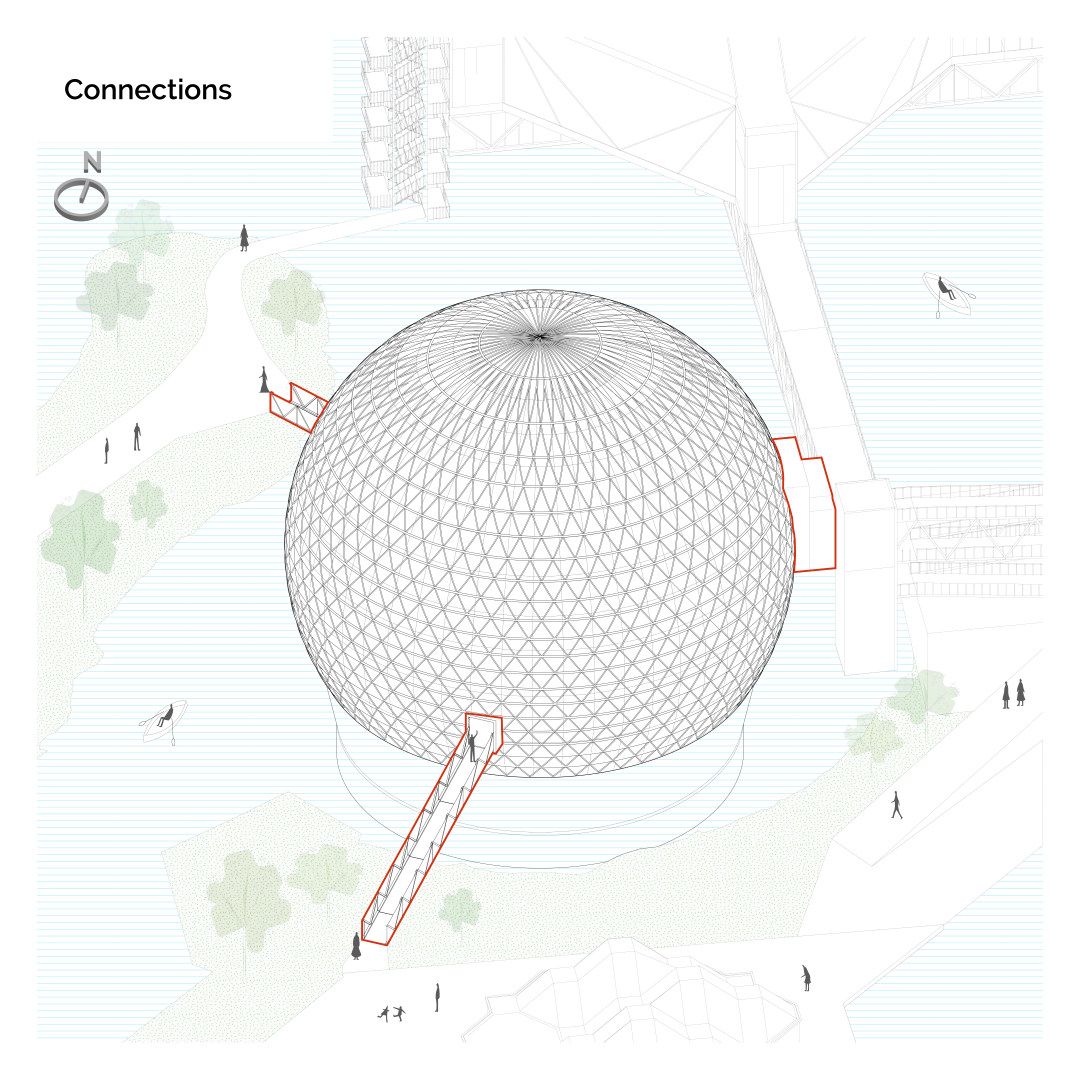

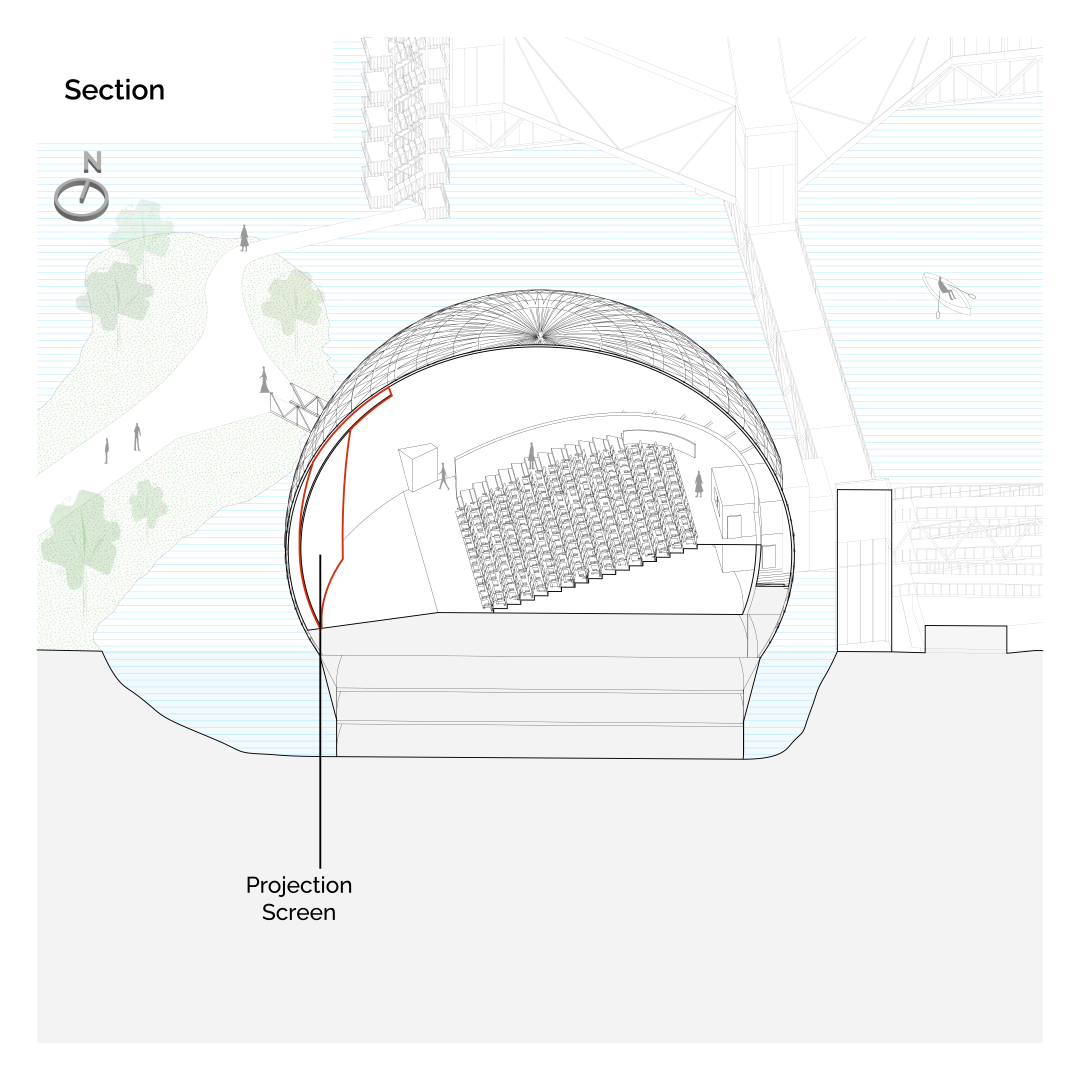

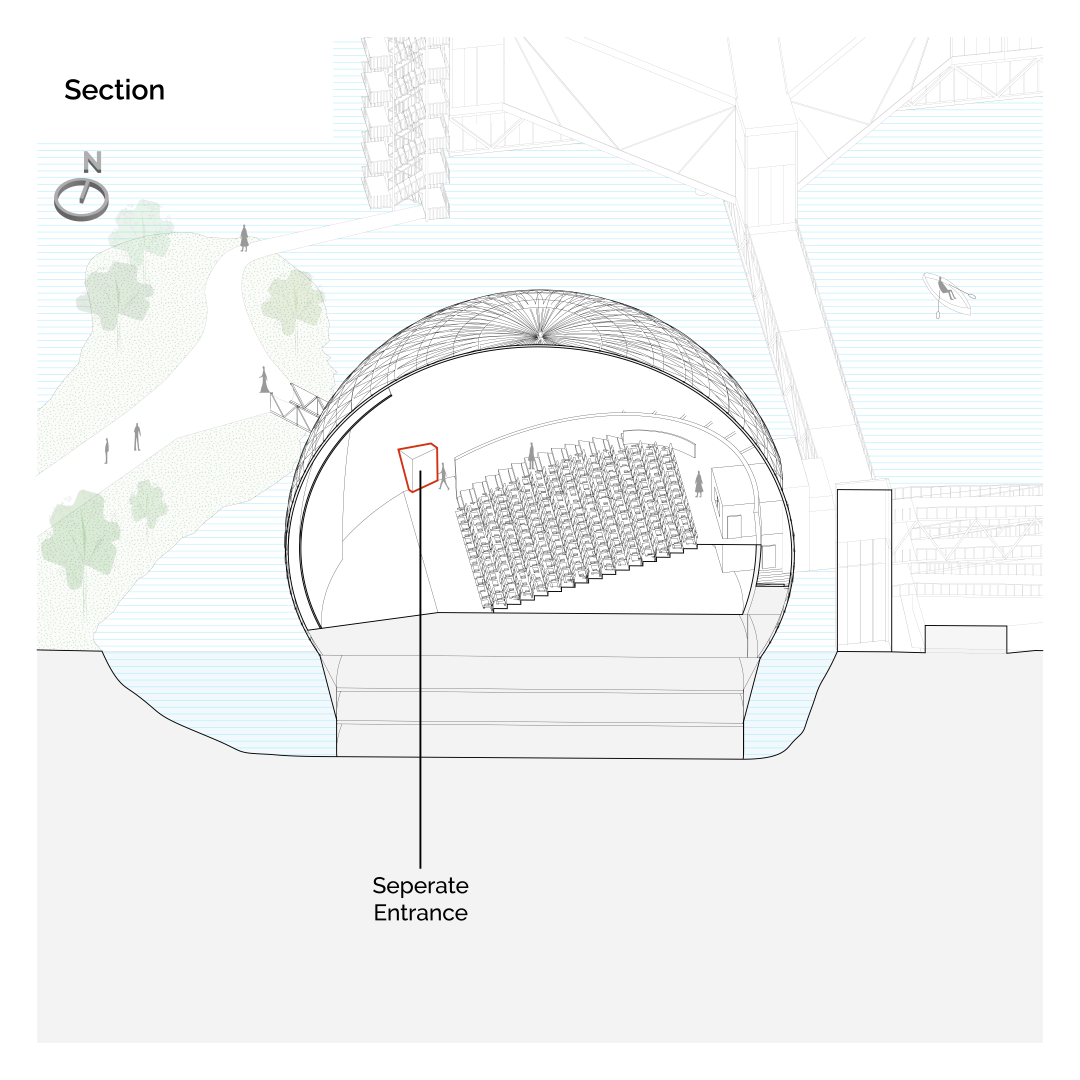

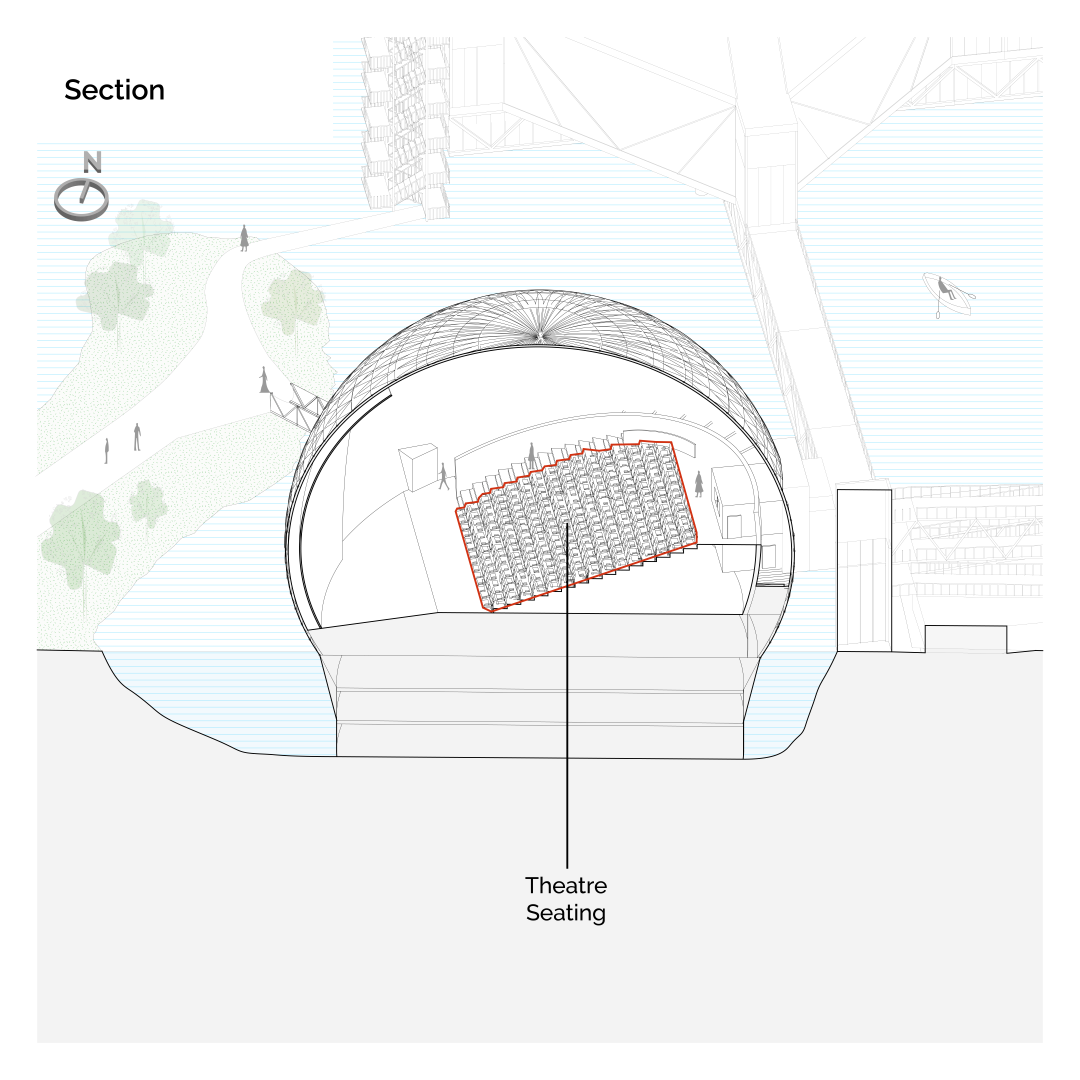

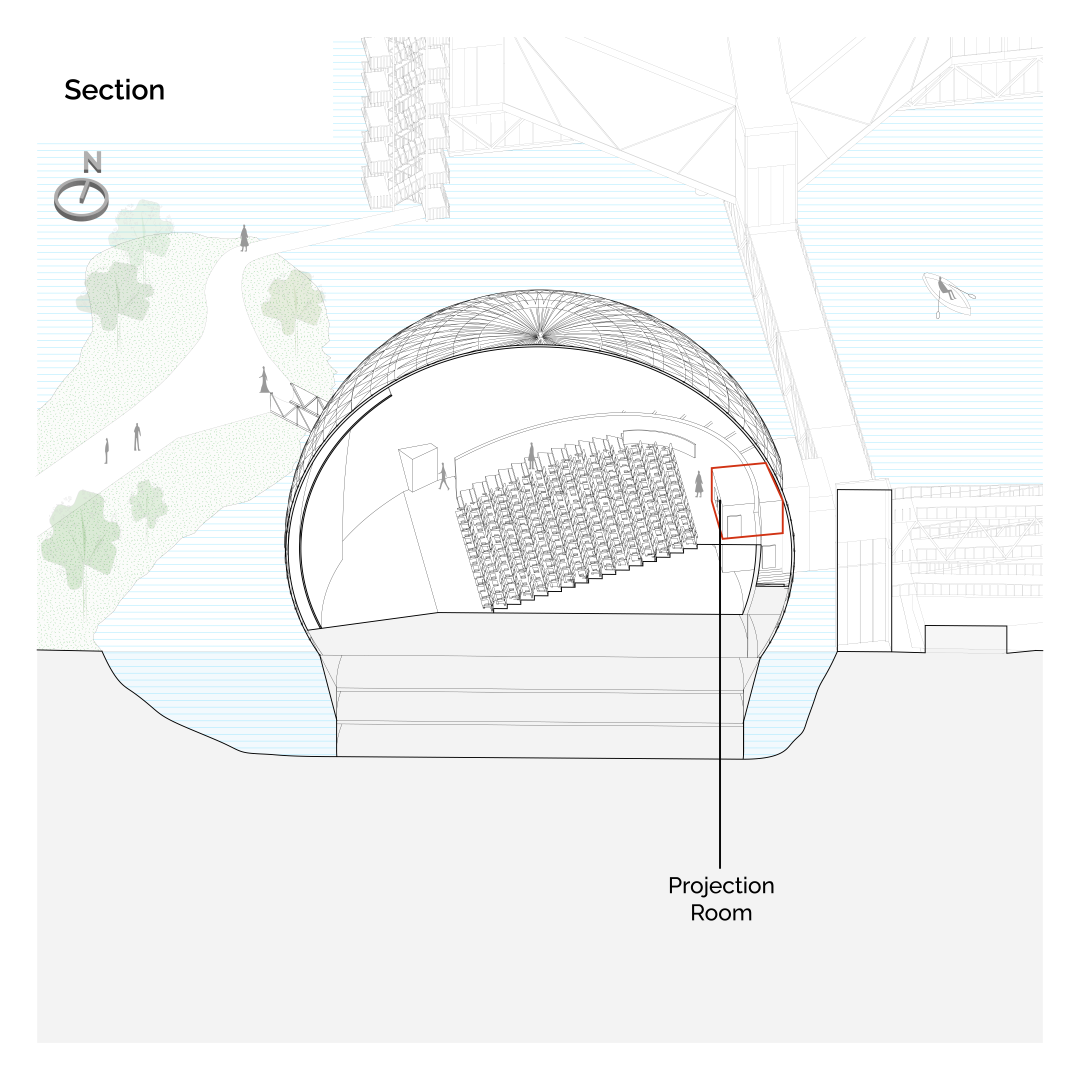

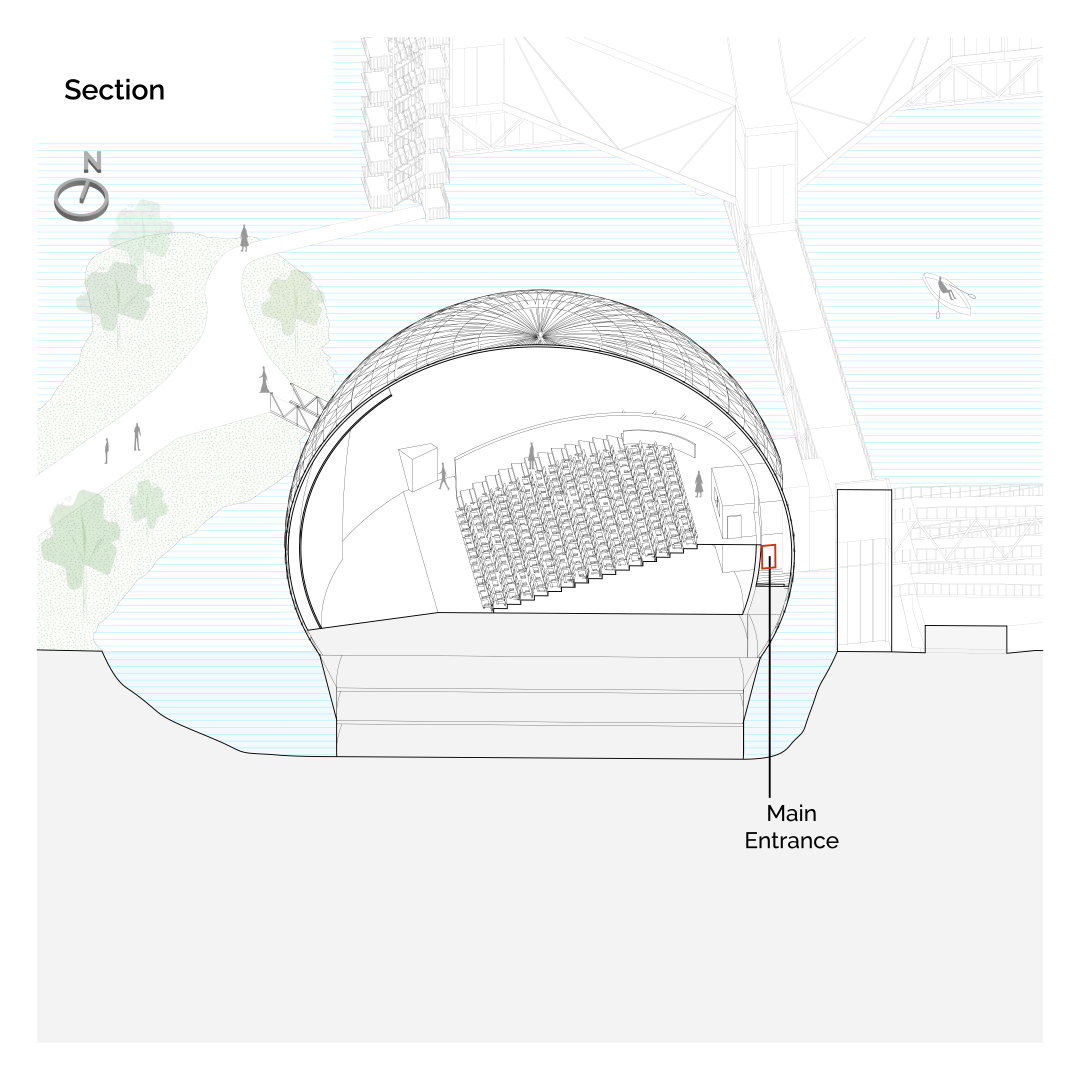

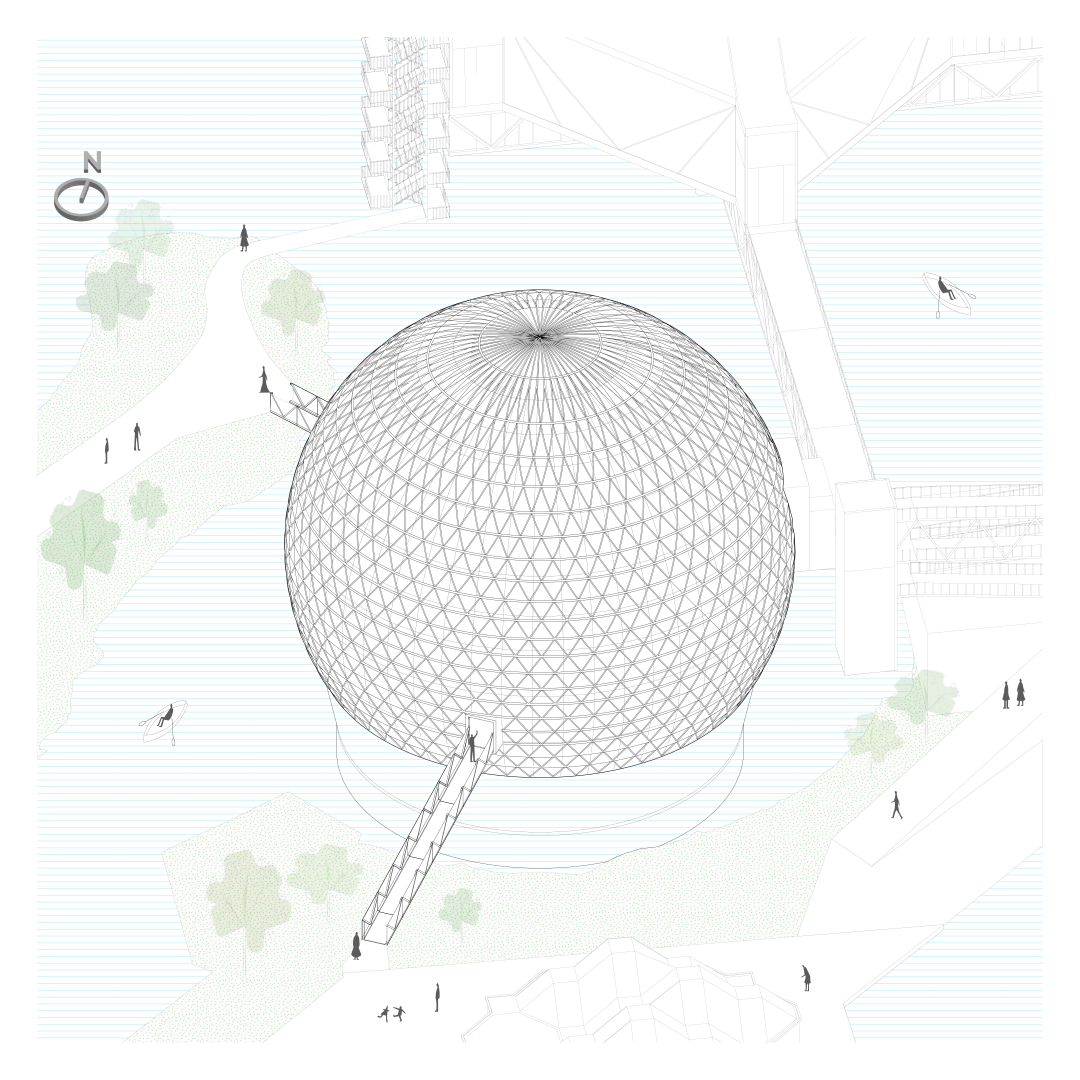

Cinesphere

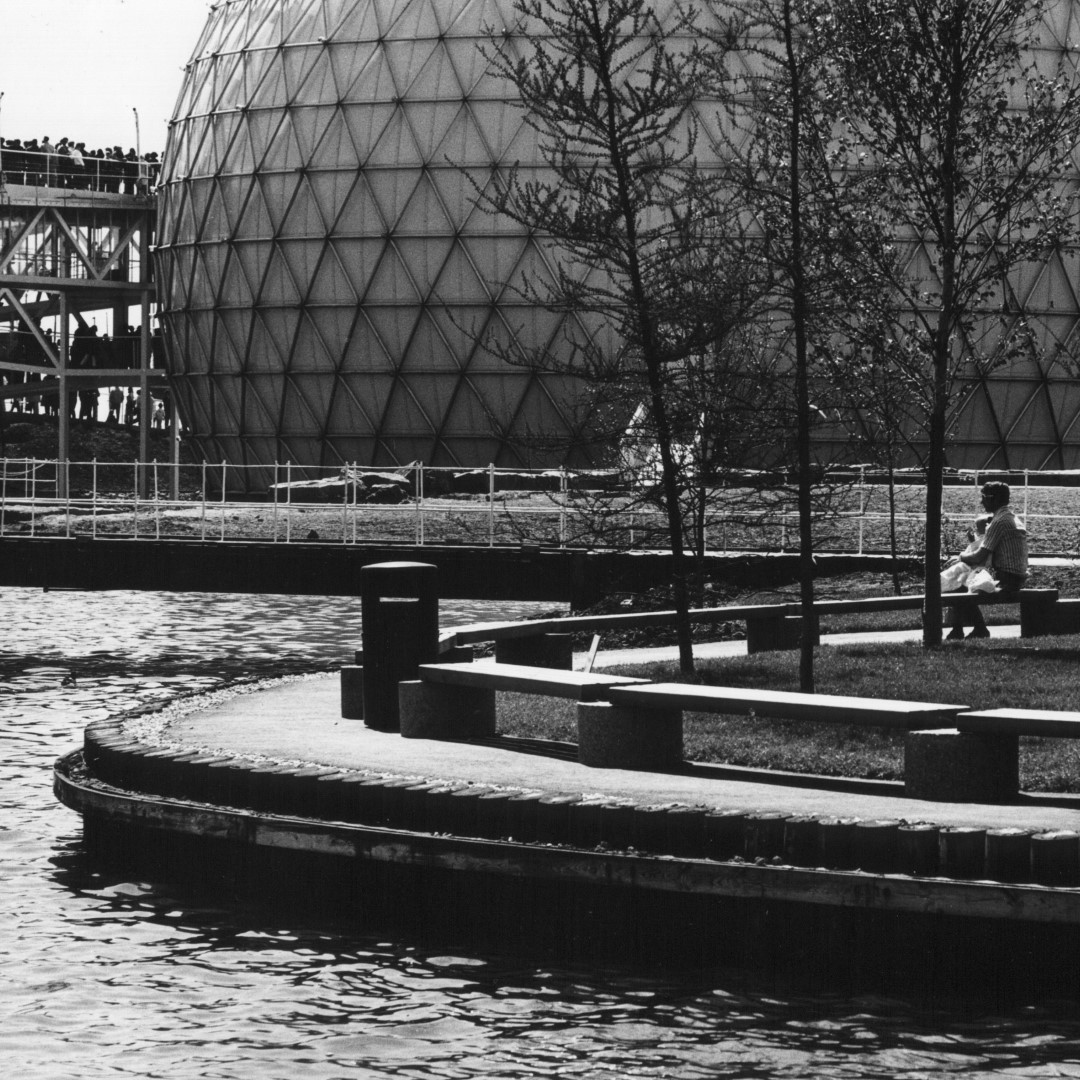

Opening in 1971, the Cinesphere at Ontario Place was a building emblematic of the future. As the first IMAX theatre in the world and an engineering marvel it became a centrepiece at Ontario Place. The first film shown at the Cinesphere was Graeme Ferguson’s North of Superior, a film commissioned especially for the occasion. In its initial run during the 1971 season, over 1.1 million visitors saw the film.

A close collaboration between architect Eberhard Zeidler and structural engineer Gord Dowell resulted in exquisite detailing- such as the triodetic shell formed by steel and aluminium tubes. The 35-metre wide semi-amphitheatre can be entered via elevated walkways which connect it to the Pods, forming a megastructure.

The Cinesphere closely resembles many radical Utopian architectural works such as Archigram’s Blow-Out Village and Buckminster Fuller’s Geodesic Dome. In contrast to the US pavilion at Expo-67, the Cinesphere’s form has a more direct relationship to its function--with interior seating and circulation following the envelope’s spherical form. The moat surrounding the Cinesphere contributes to its structural quality by creating opportunities for spectacular reflections. Lights are attached to the cladding at the intersections of the steel and aluminum rods, creating a glowing effect at night. Notable merits for the Cinesphere include a Canadian Architect Award of Excellence in 1971, an Ontario Association of Architects 25-year Award in 1999, and most recently the Prix du Xxe Siecle from the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada and the National Trust in 2017 (along with the Pods.) The Cinesphere is one of the only original buildings on site still active, made possible by a Gow Hastings Architects renovation in 2011.

Children’s Village

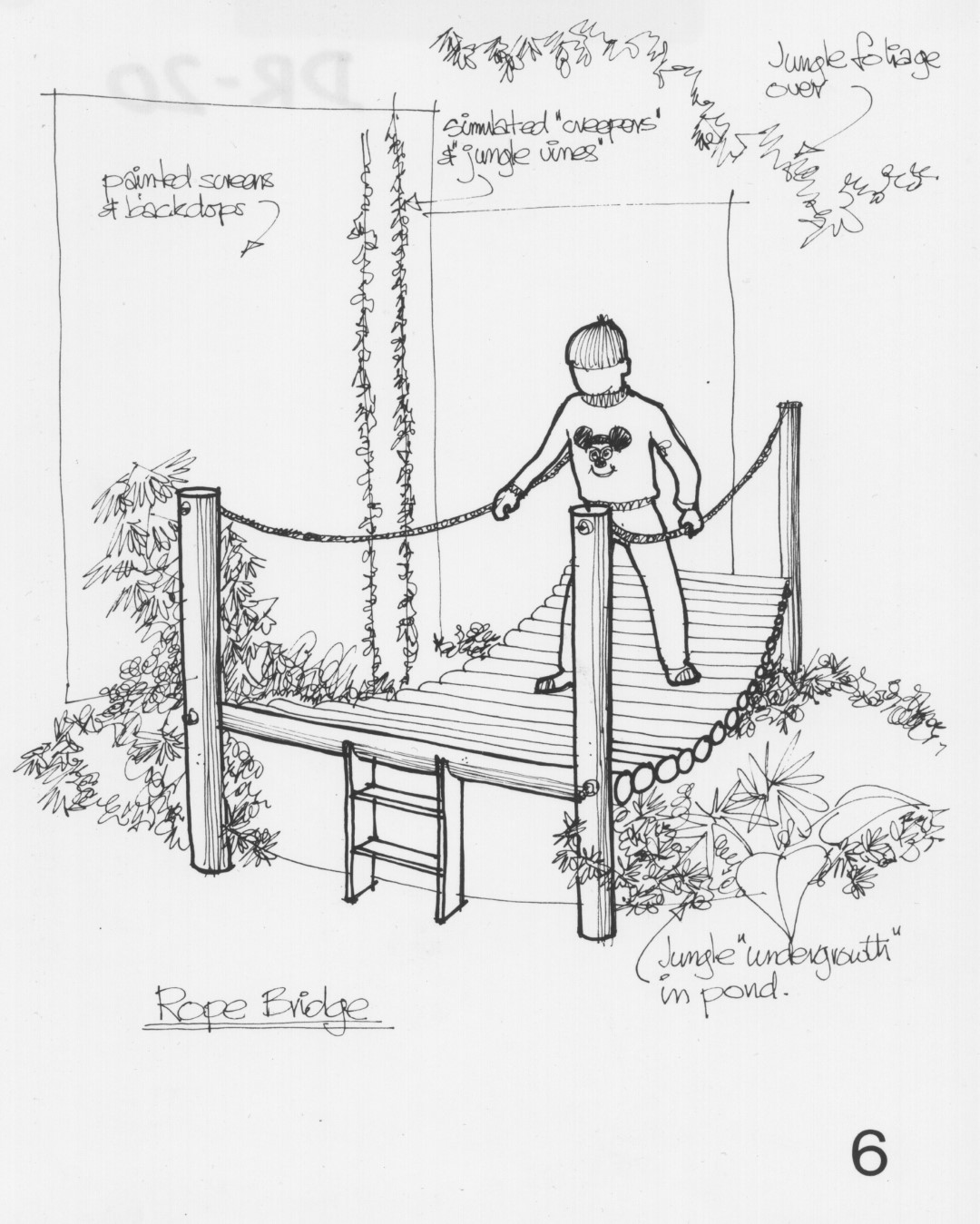

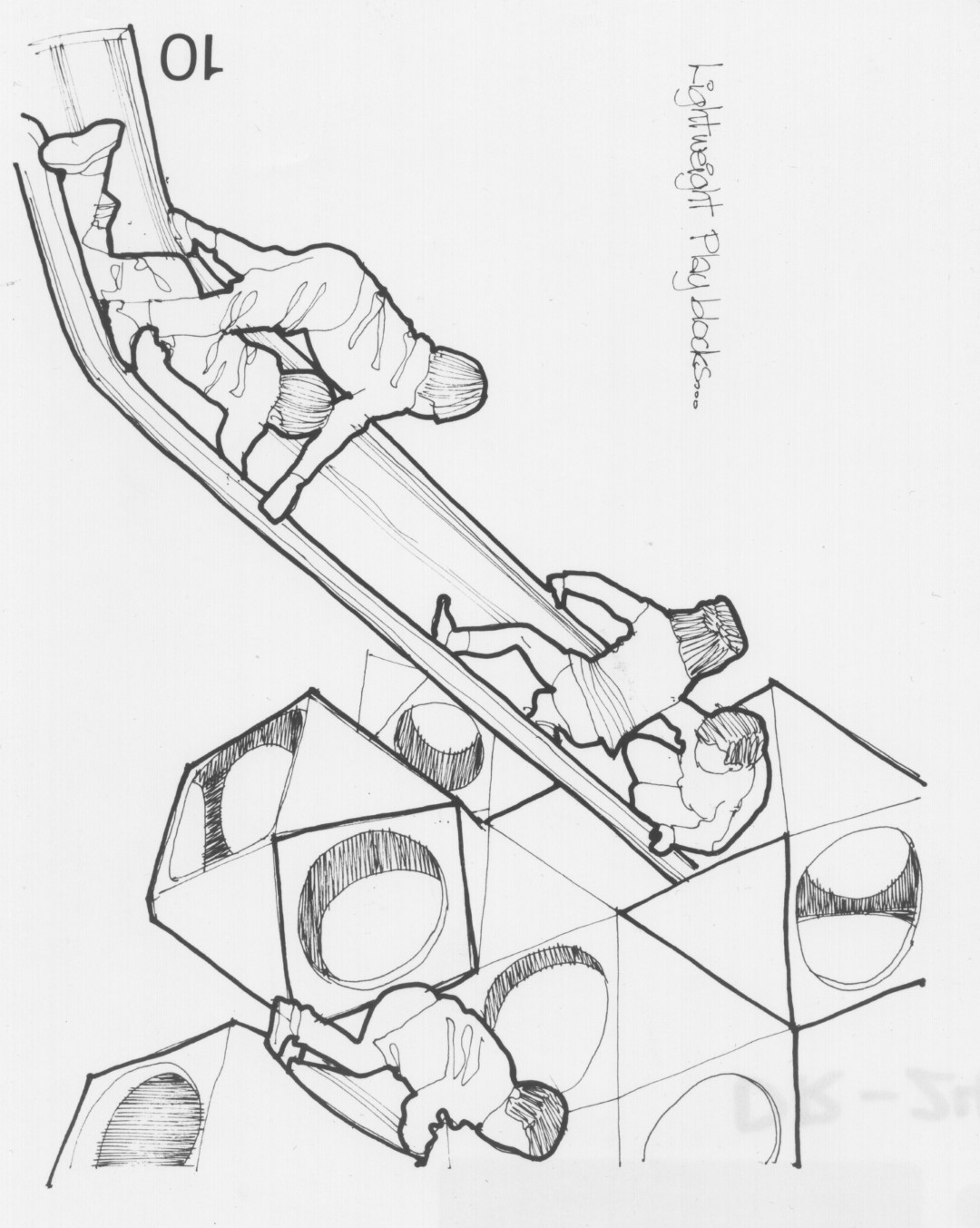

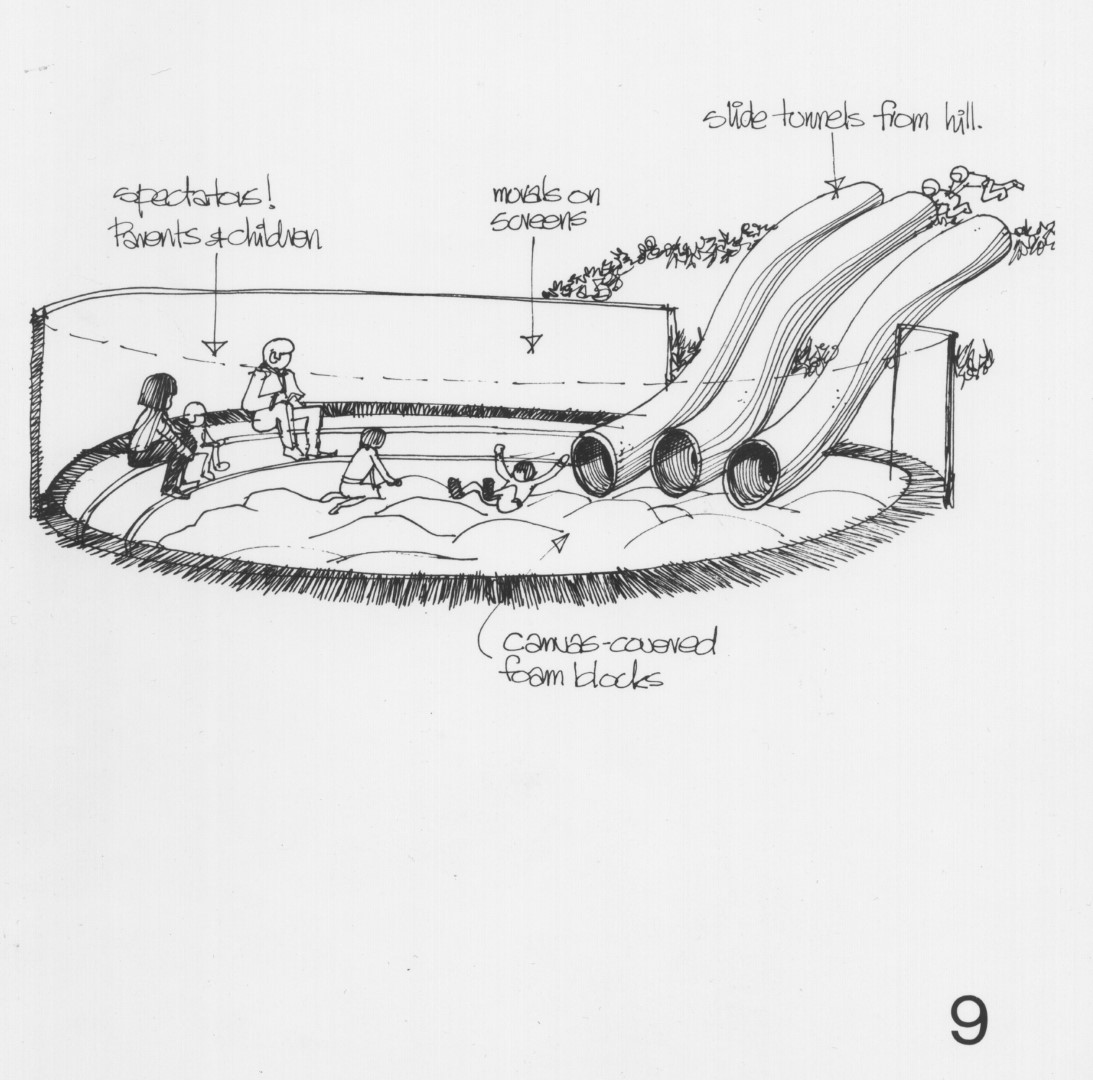

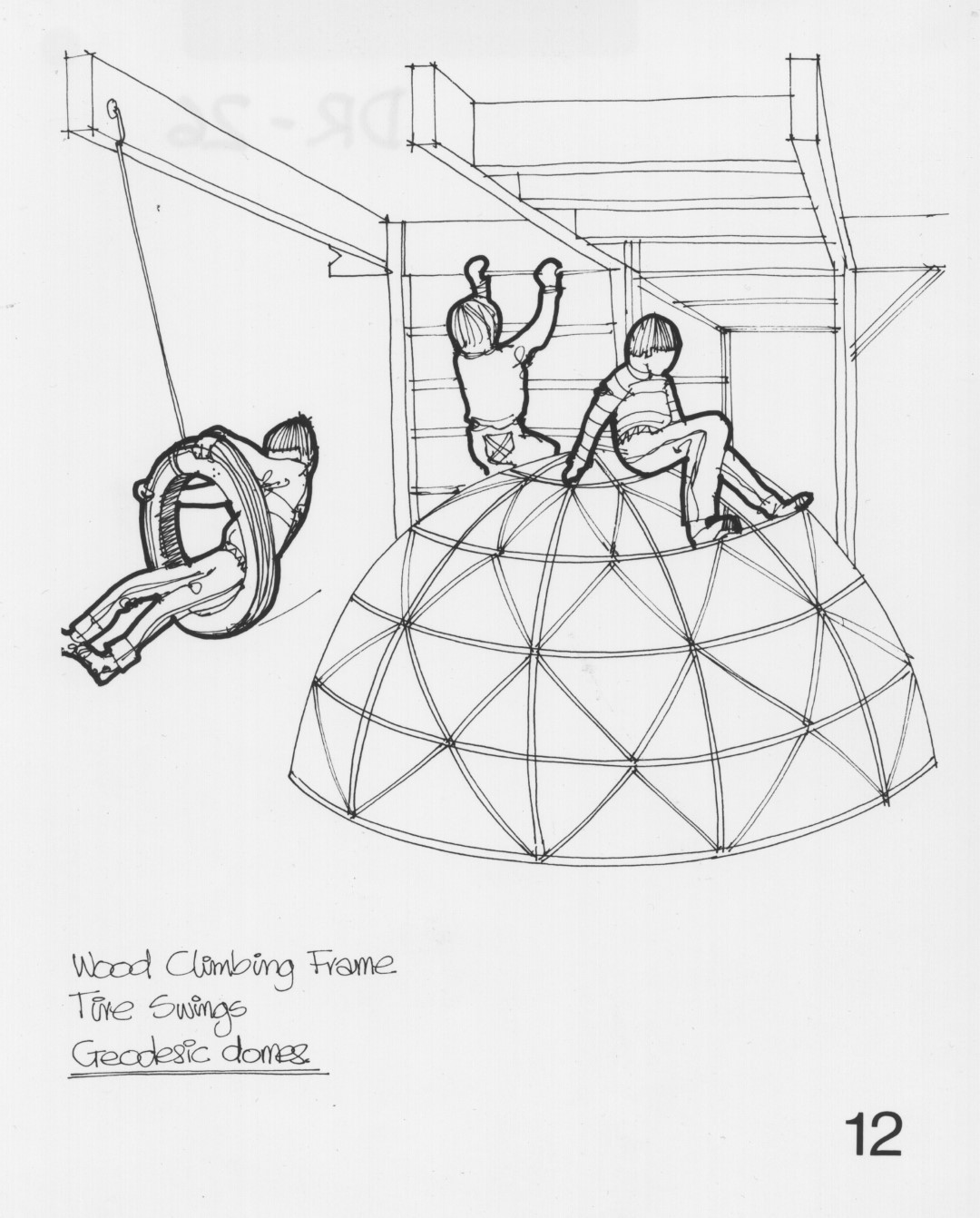

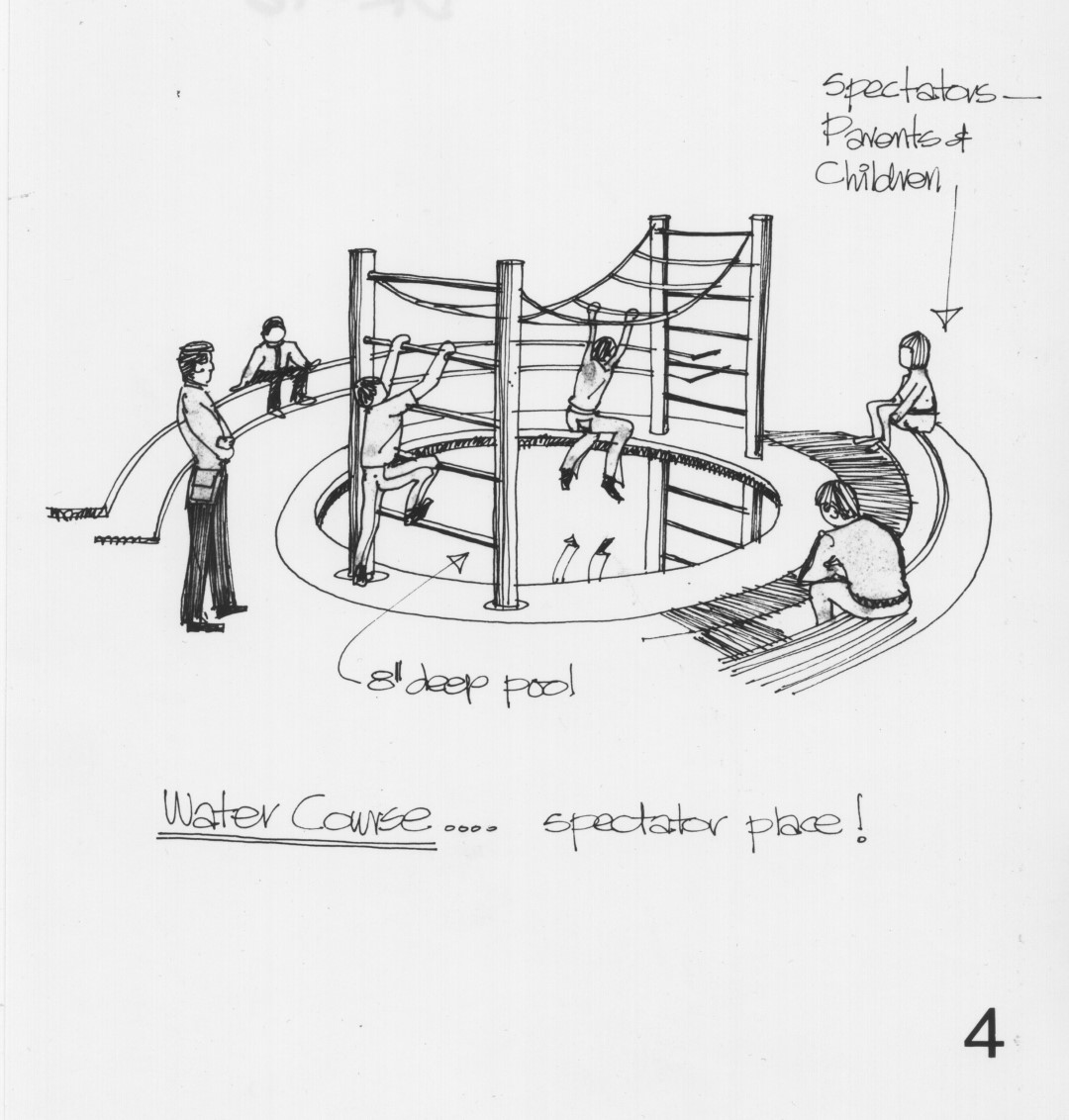

Known as “the father of soft play”, Eric McMillan’s design for the Children’s Village revolutionized children’s playscapes. The Children’s Village was part of the original masterplan by Eberhard Zeidler, although it was moved to a later phase of the project due to budgetary constraints. Opening in 1973, McMillan’s Children’s Village provided critical programming for children at a time when activities at Ontario Place were otherwise oriented towards older users.

McMillan’s inspiration for the Children’s Village came from his experience as a child, creating ad hoc games in a neighbourhood that offered no other form of entertainment. From “punching bag forests”, to ziplines, and climbing ropes, the Children’s Village was designed as a scaffold, providing space for children’s imaginations to flourish. Due to the success of the original Children’s Village, McMillan was asked to create an adjacent water play area.

The Children’s village was incrementally destroyed, with the last remnant disappearing in 2002 to make room for junior midway rides in an attempt to generate more profit.

You can view footage of the Children’s Village in our archive.

Sketches of the Children’s Village were provided by Zeidler Architects Inc.

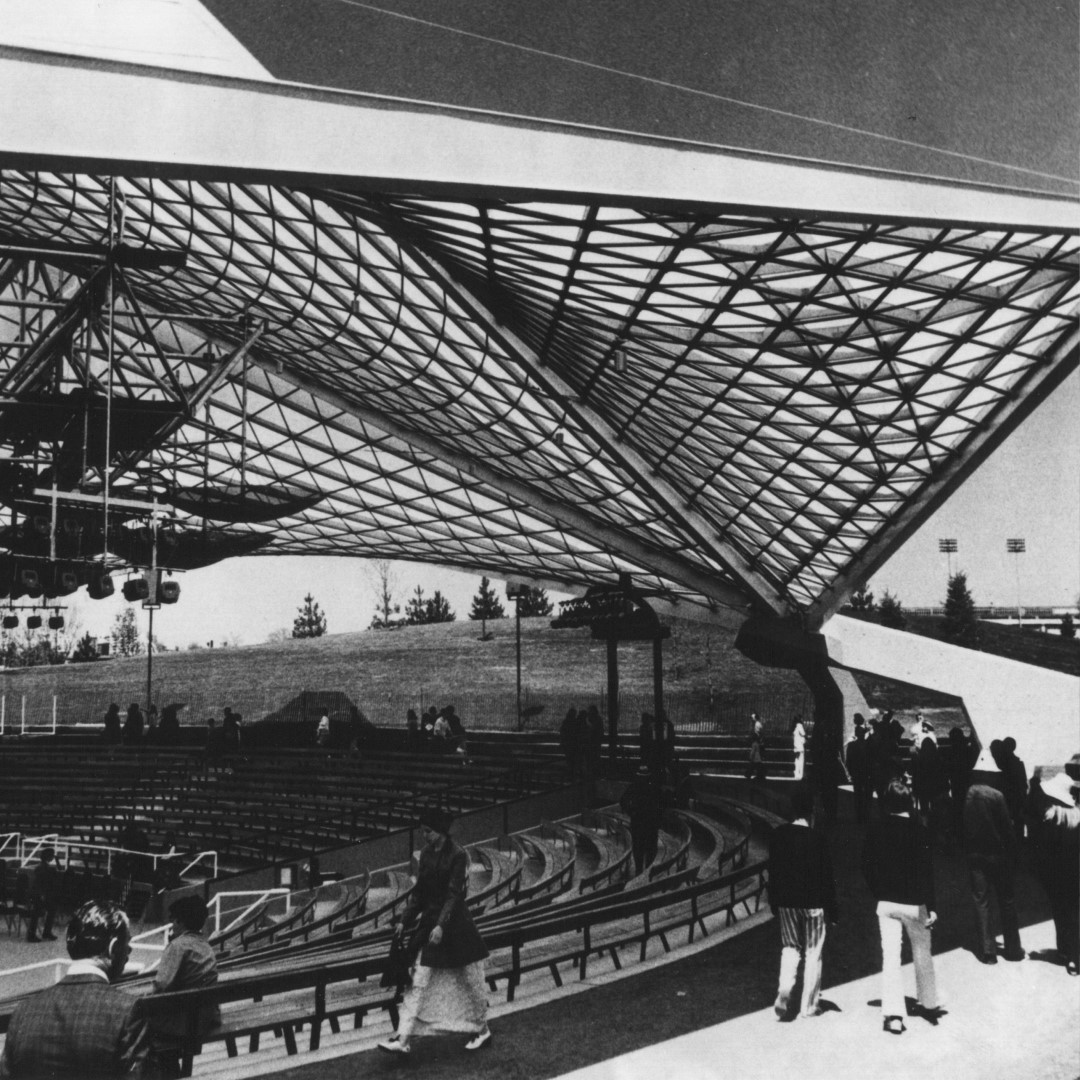

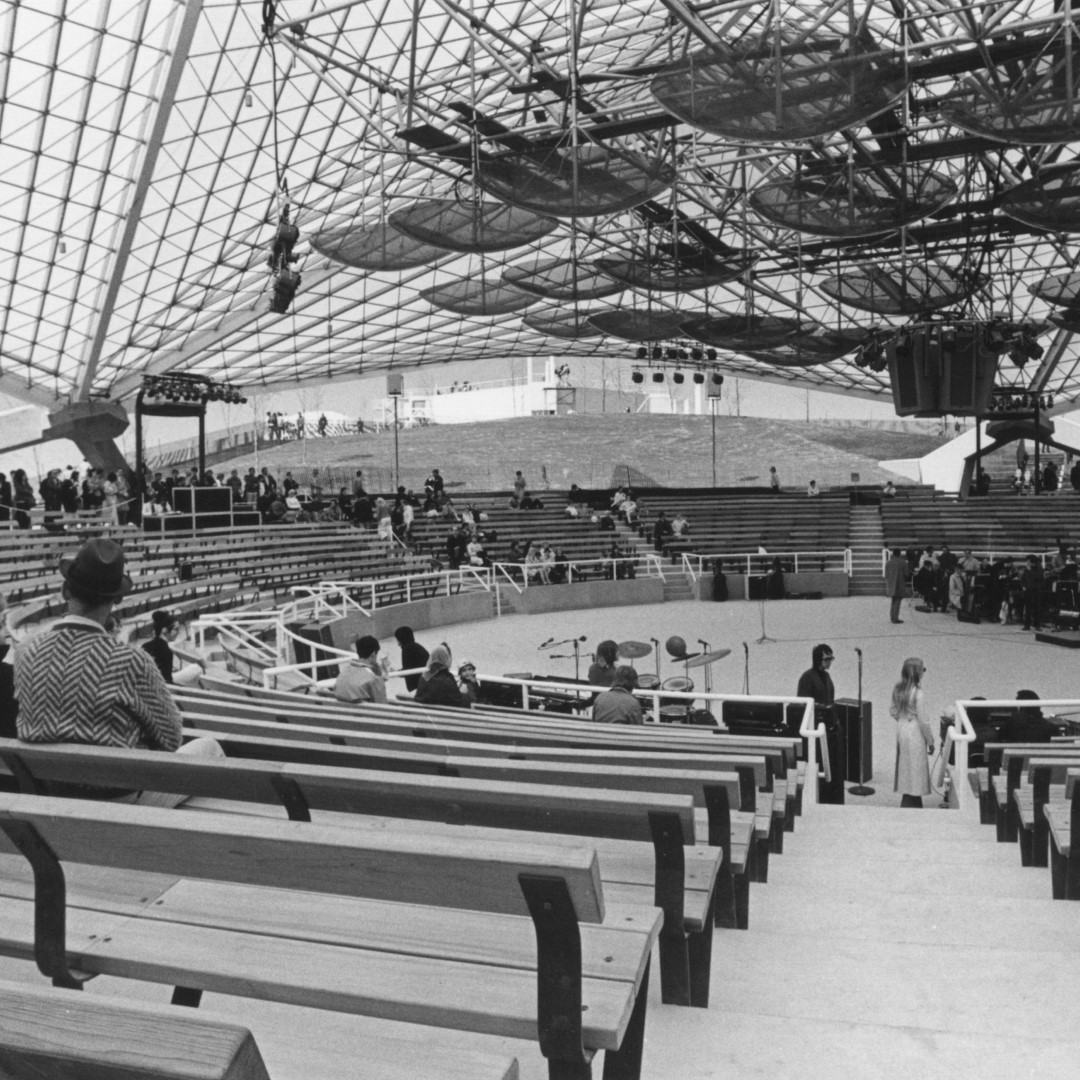

Forum

From 1971 to 1994 the Forum stood as a popular open-air amphitheatre on the East Island. The amphitheatre sat inside a basin formed by hills sloping down towards the rotating stage. This arrangement allowed for 8000 to be comfortably seated around the stage, making the Forum a popular music venue in the city. The Toronto Symphony Orchestra regularly played at the Forum, along with iconic acts such as BB King, Glen Campbell, Kenny Rogers, Johnny Cash, Bruce Cockburn, James Brown, Men Without Hats, and more. In 1984, a riot broke out at the Forum during a Teenage Head performance. Subsequently ‘hard rock’ acts were banned, and the venue became synonymous with classical, jass, and pop performances.

In 1992 MCA International and Molson Breweries began a joint venture to redevelop the Forum. This was met with protestations from the original designers, community members, architects, environmentalists and others. A group known as Friends of the Forum which included Jane Jacobs, Eberhard Zeidler, and Michael Hough opposed the development- as it would destroy 400 old-growth trees as well as an iconic piece of architecture and landscape design. In 1994 the Forum and surrounding trees were demolished, making way for the Molson Amphitheatre- later renamed the Budweiser Stage.

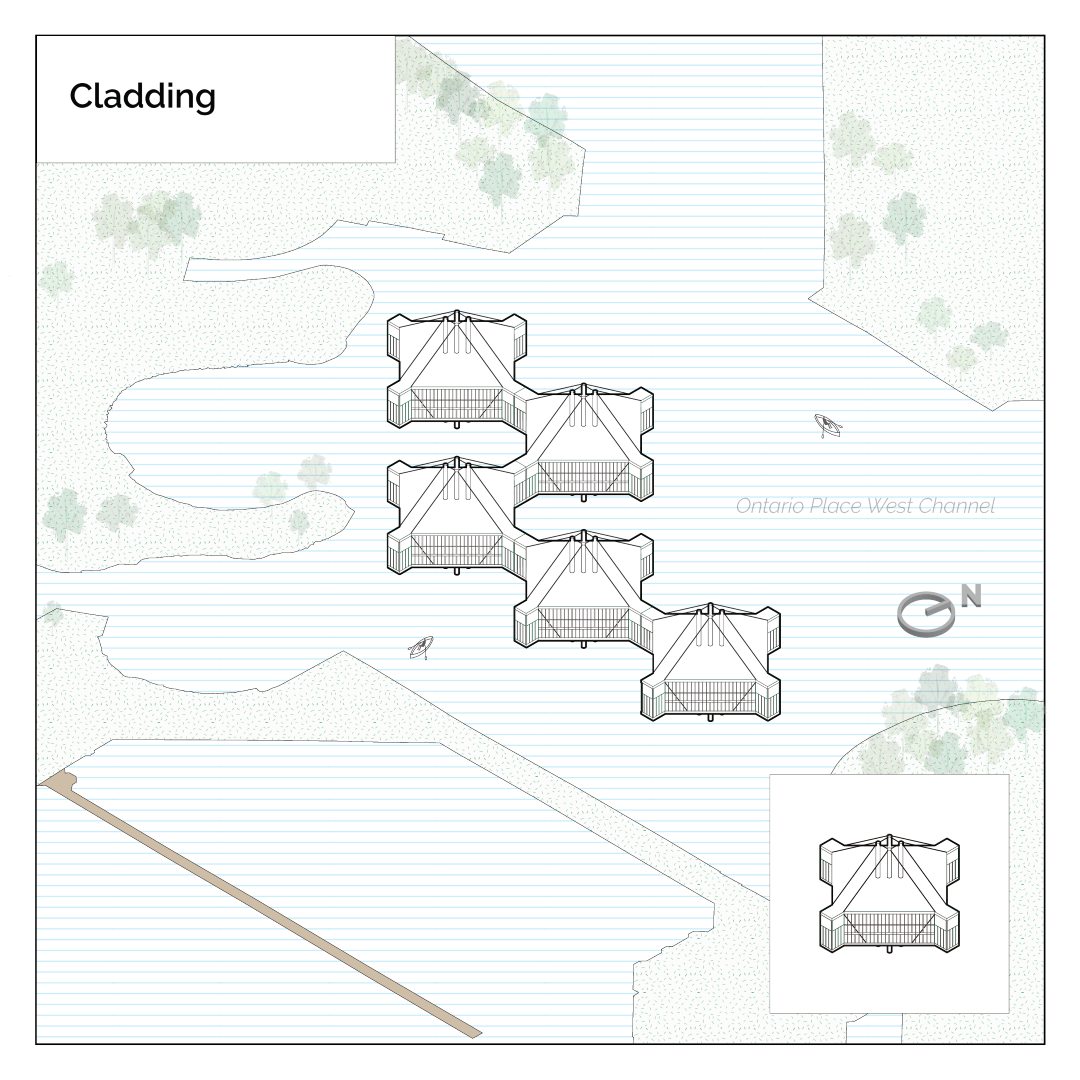

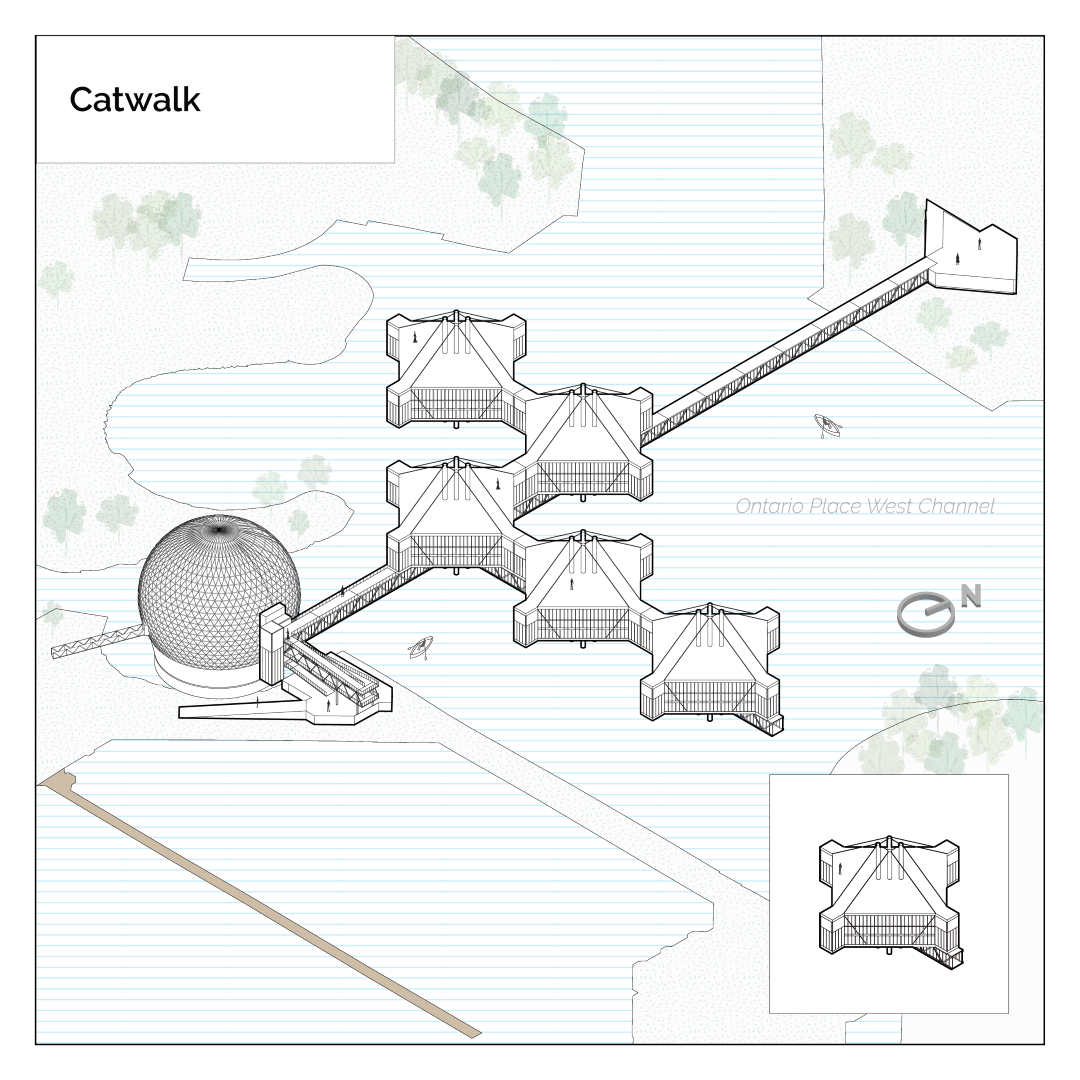

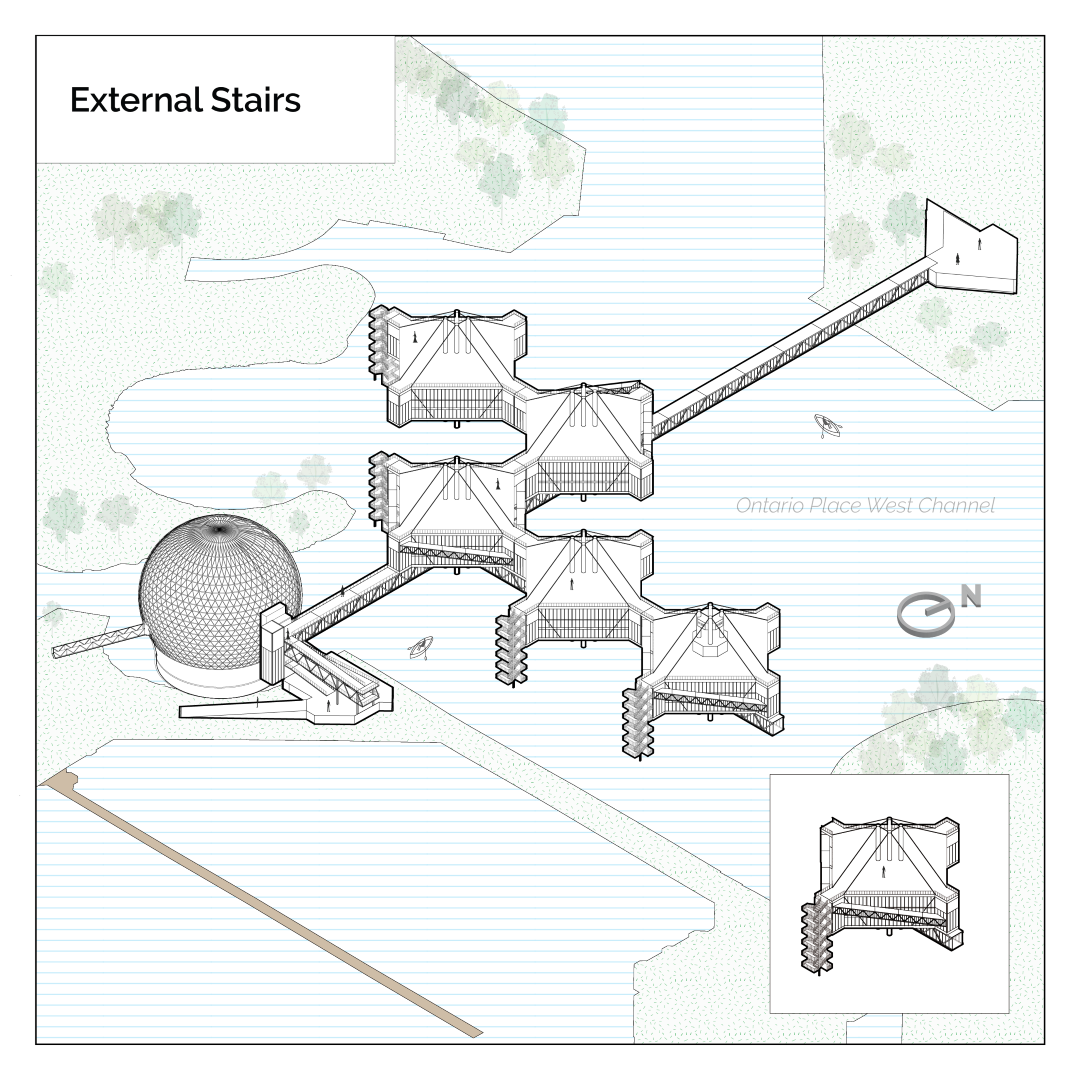

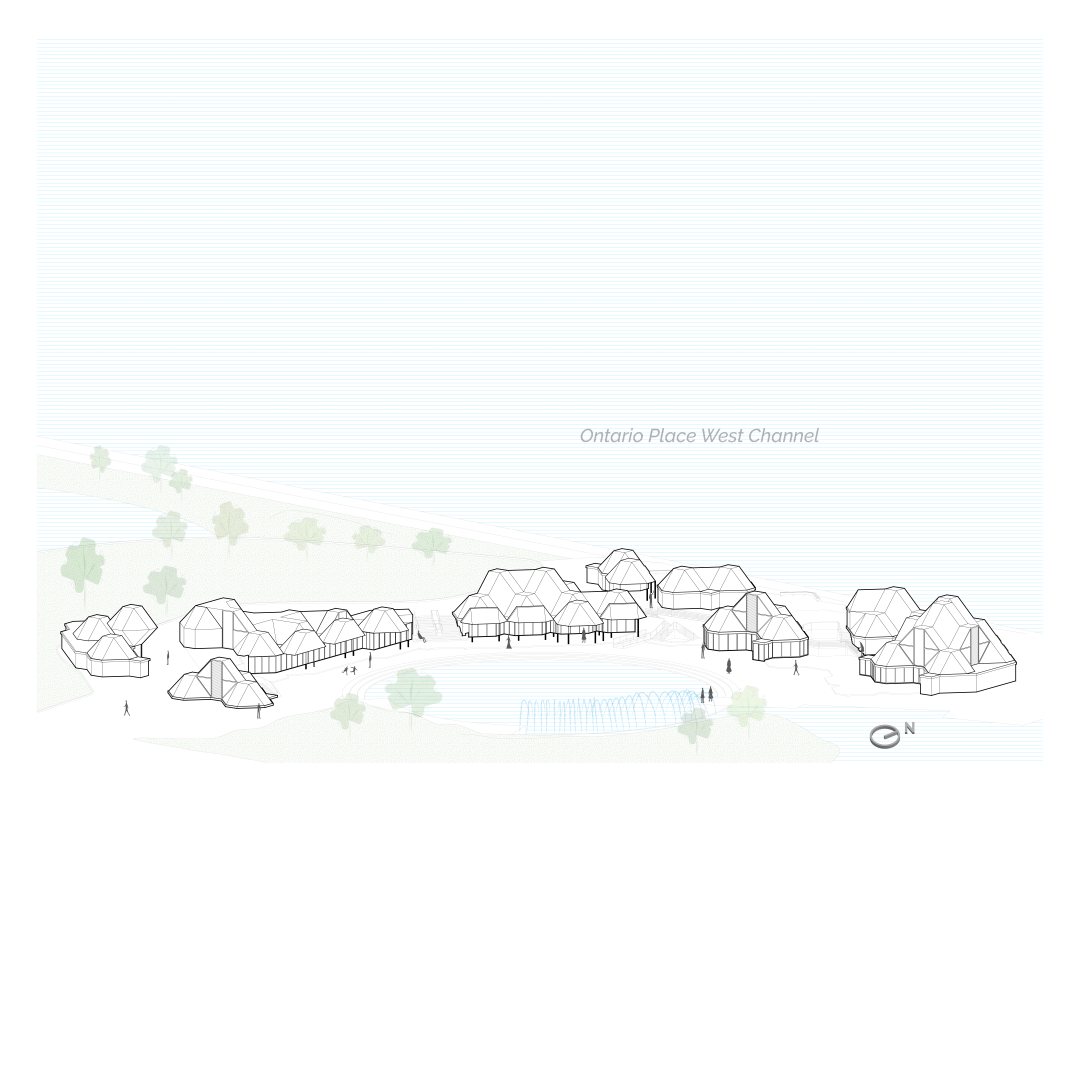

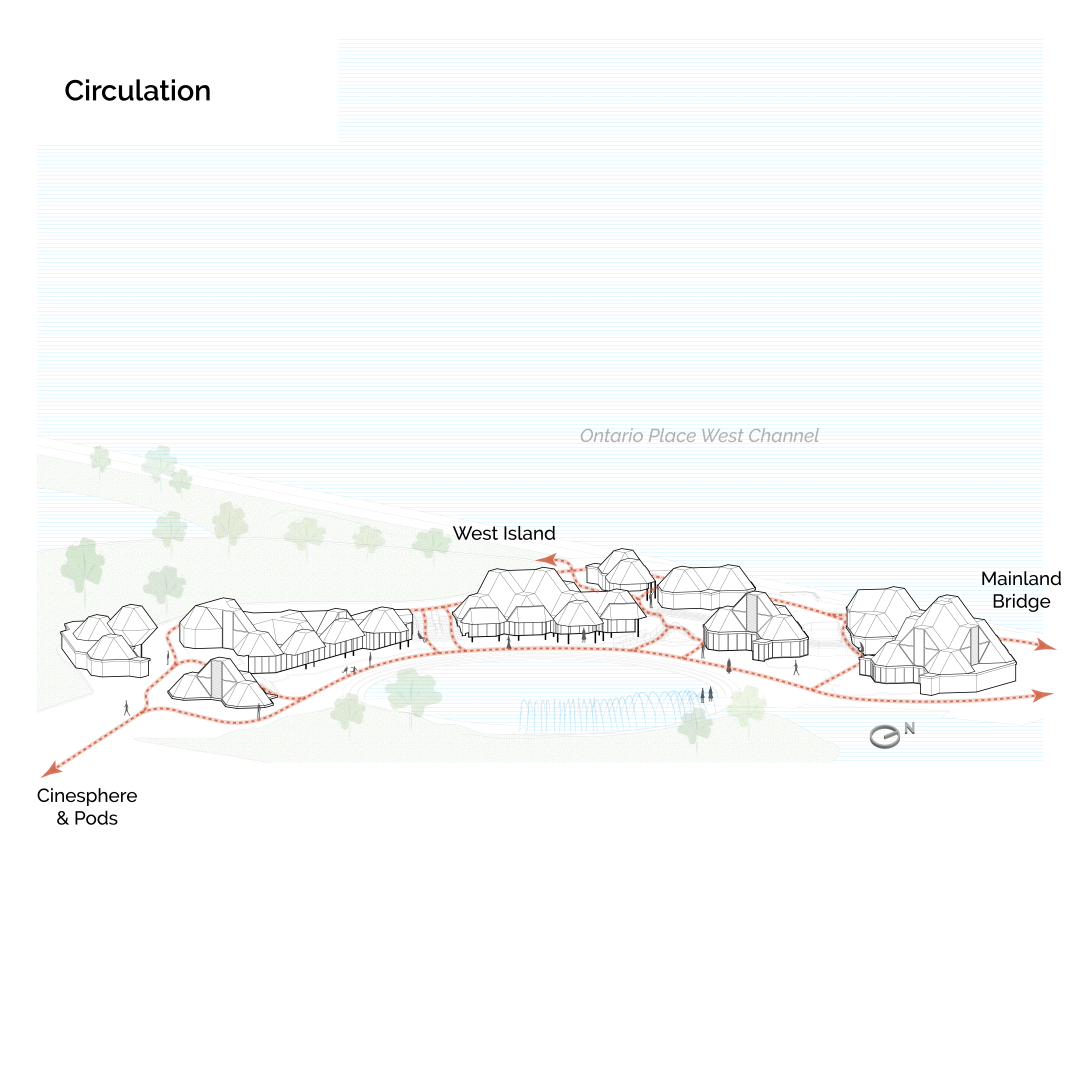

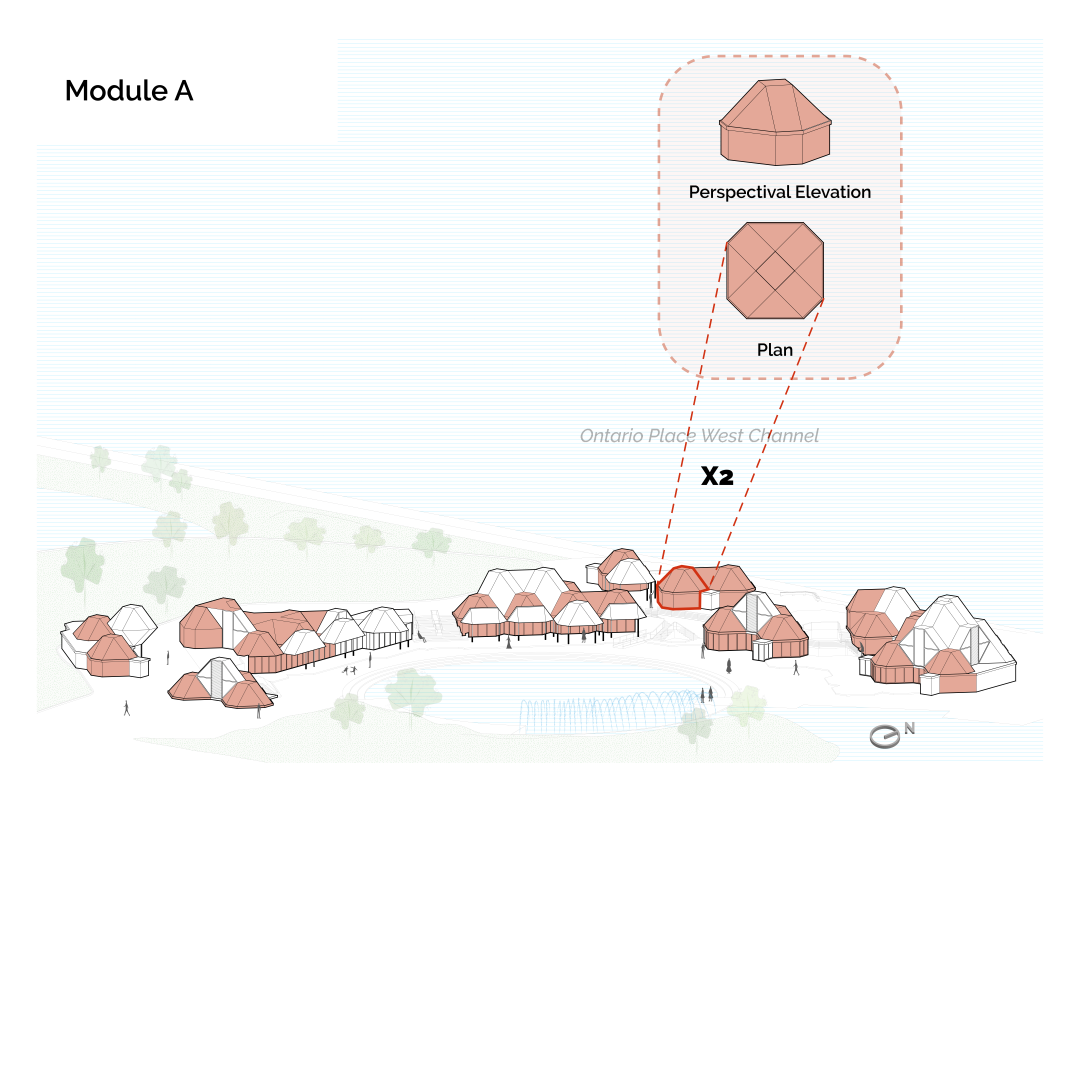

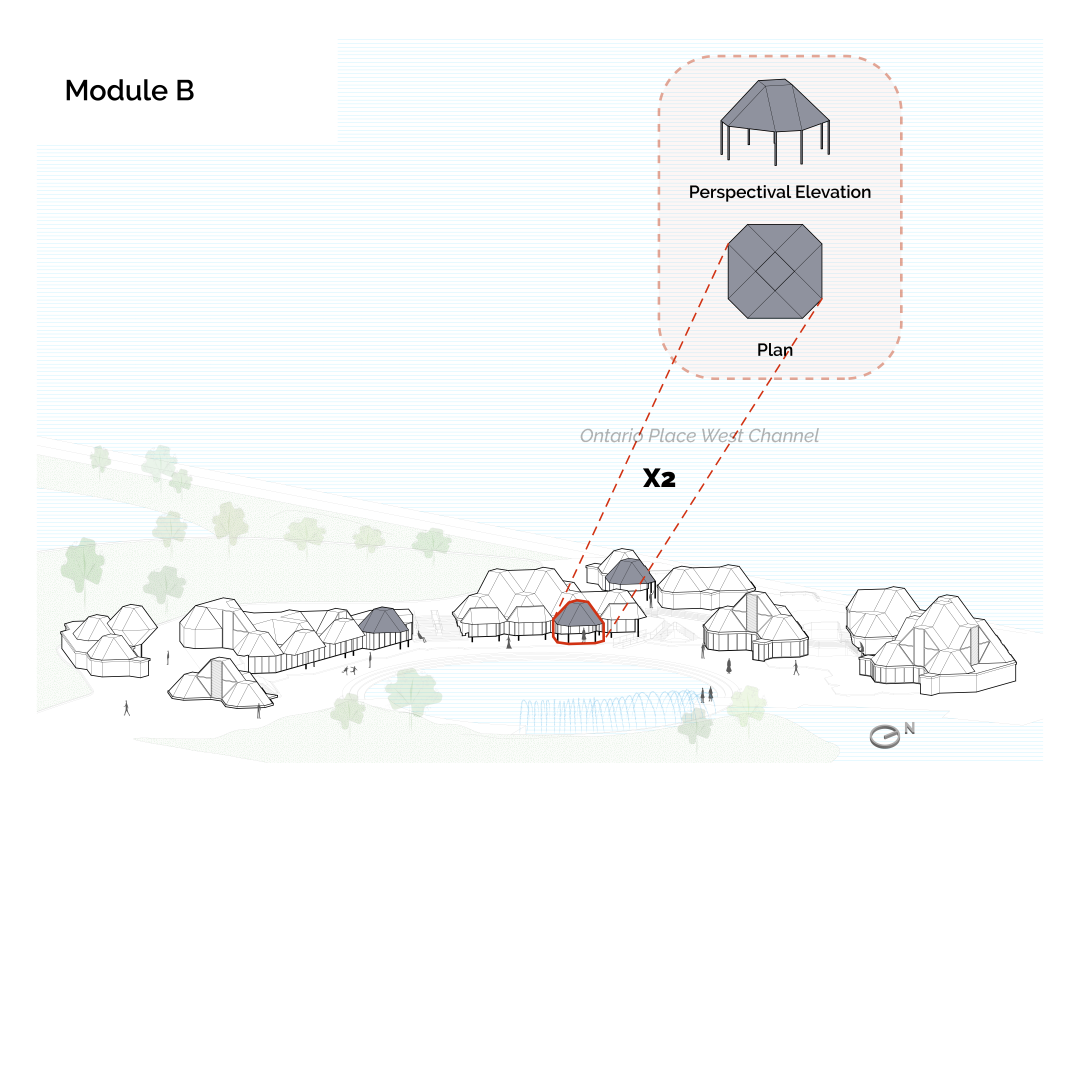

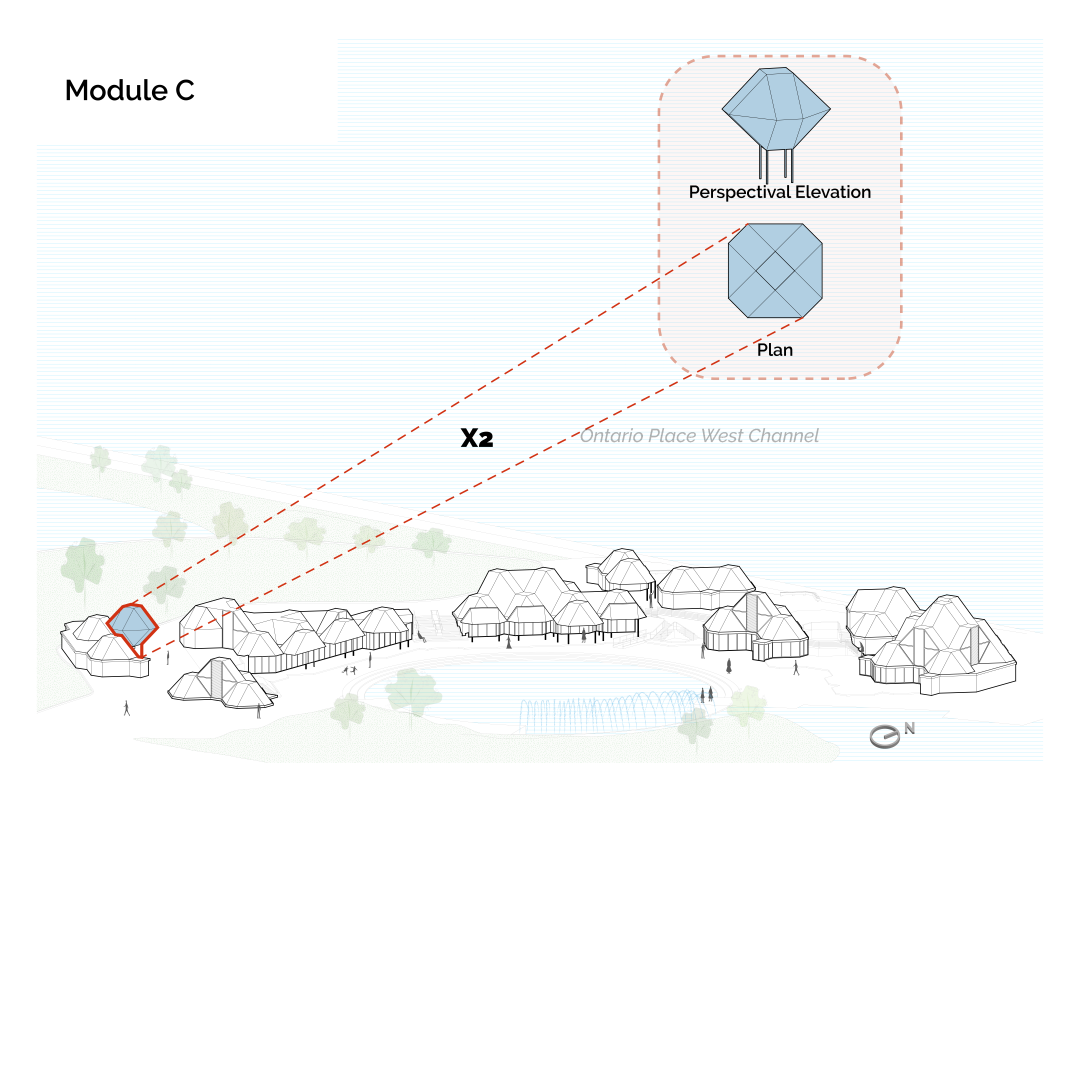

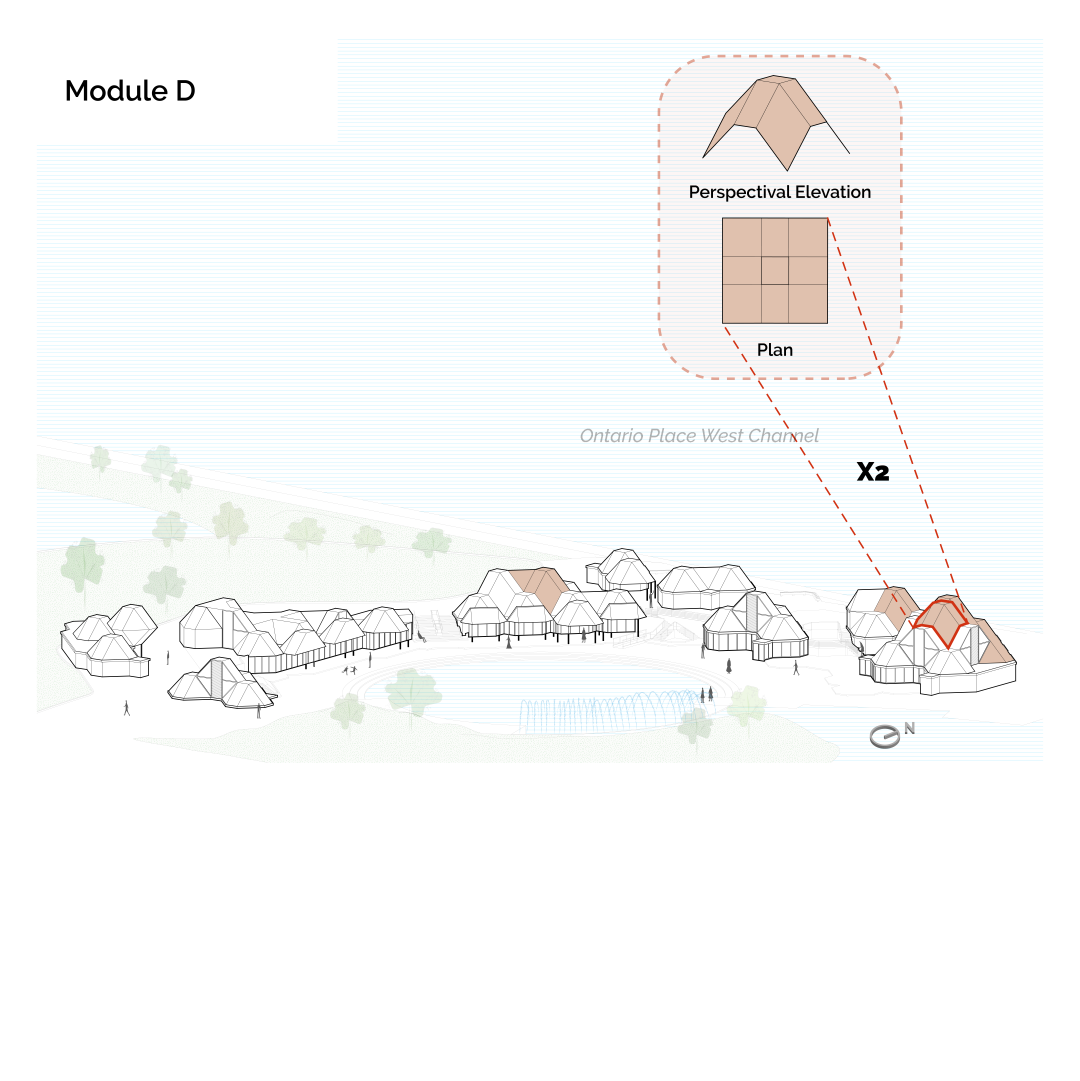

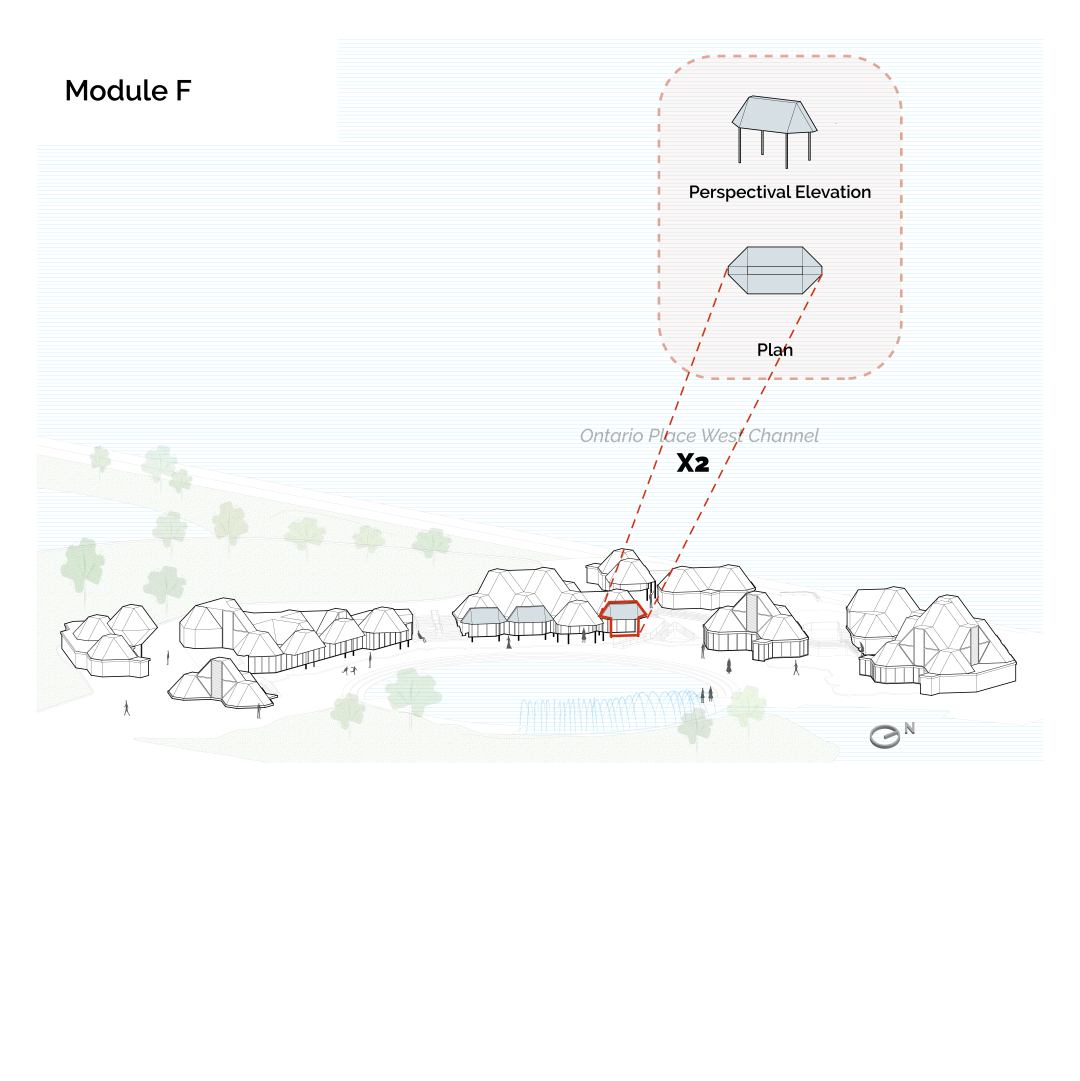

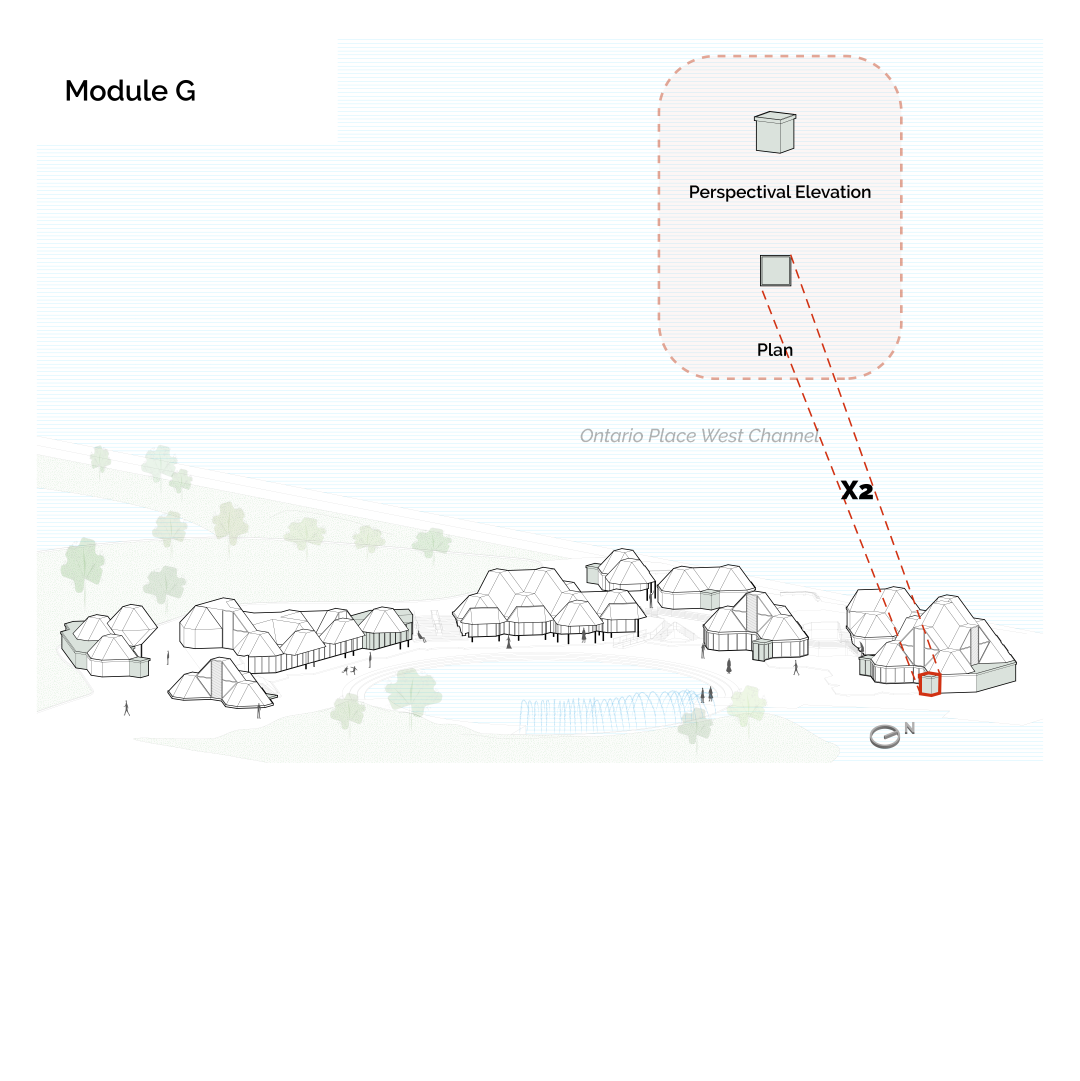

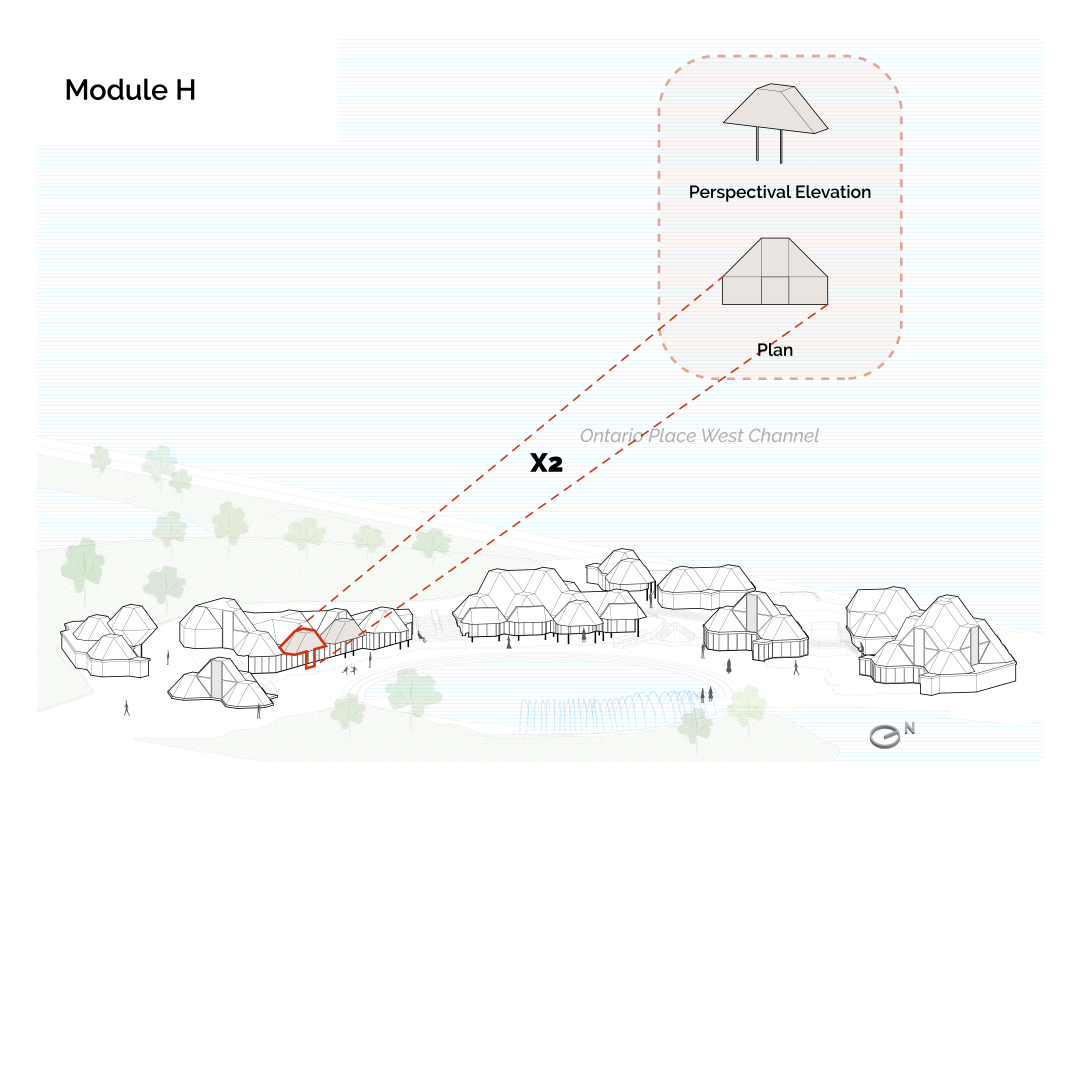

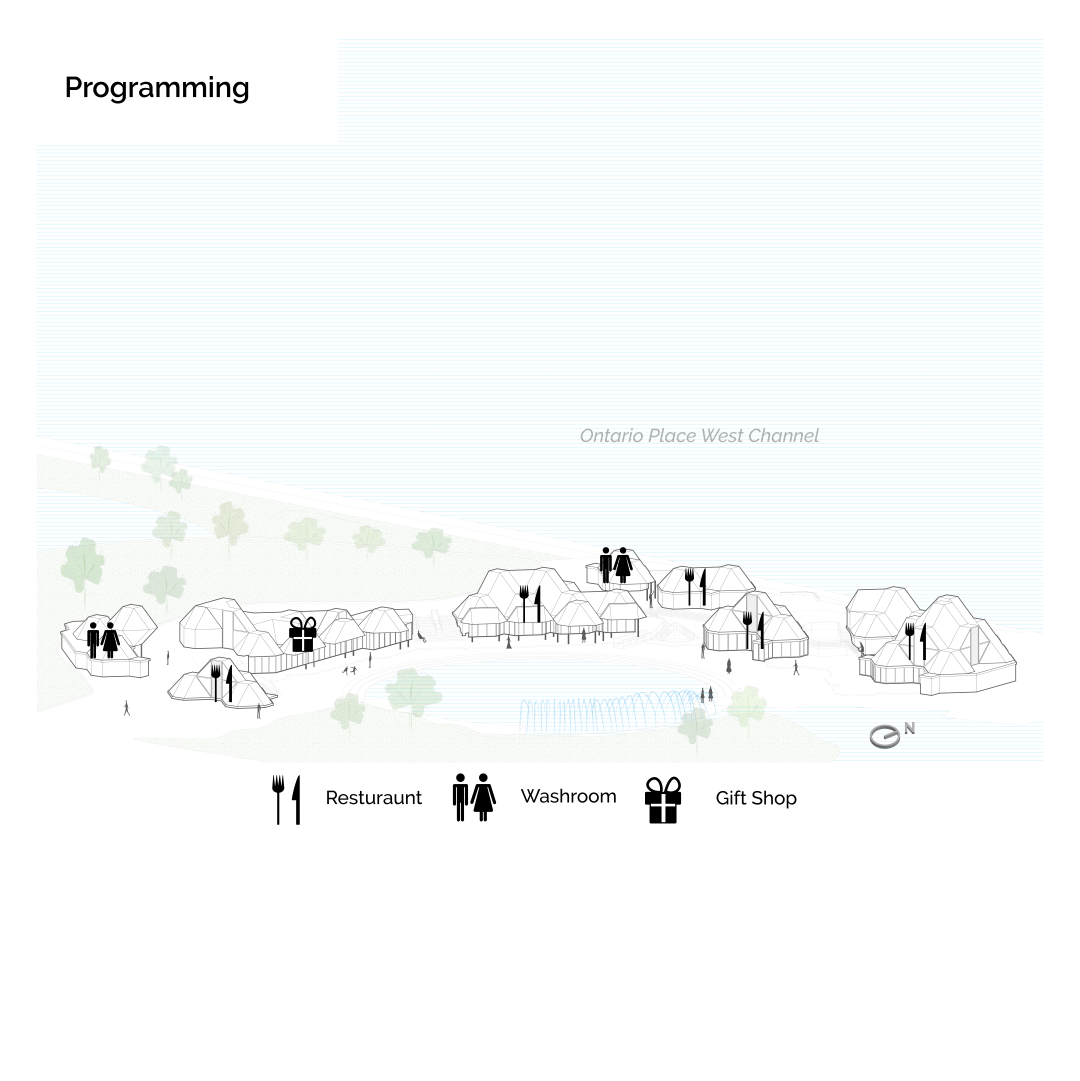

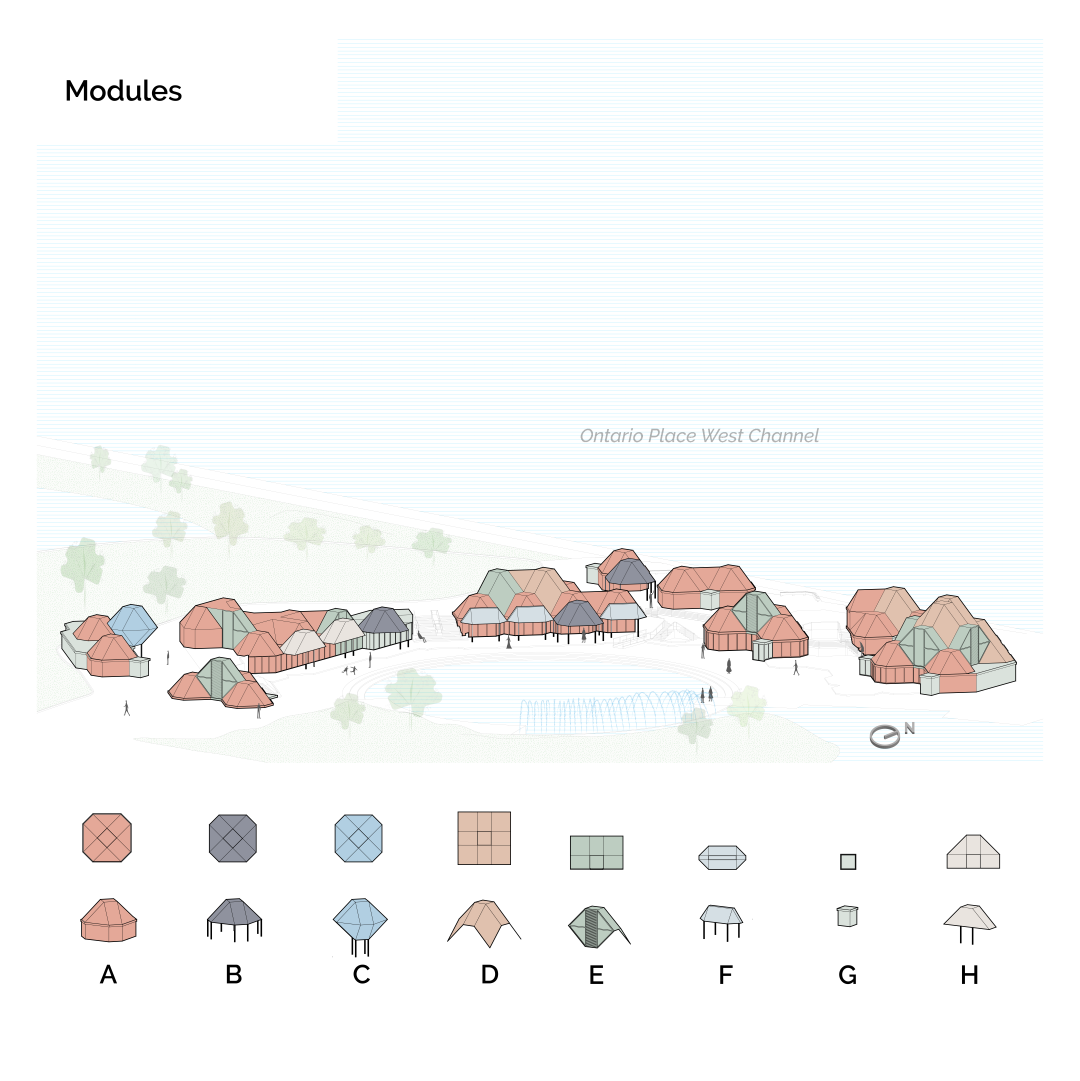

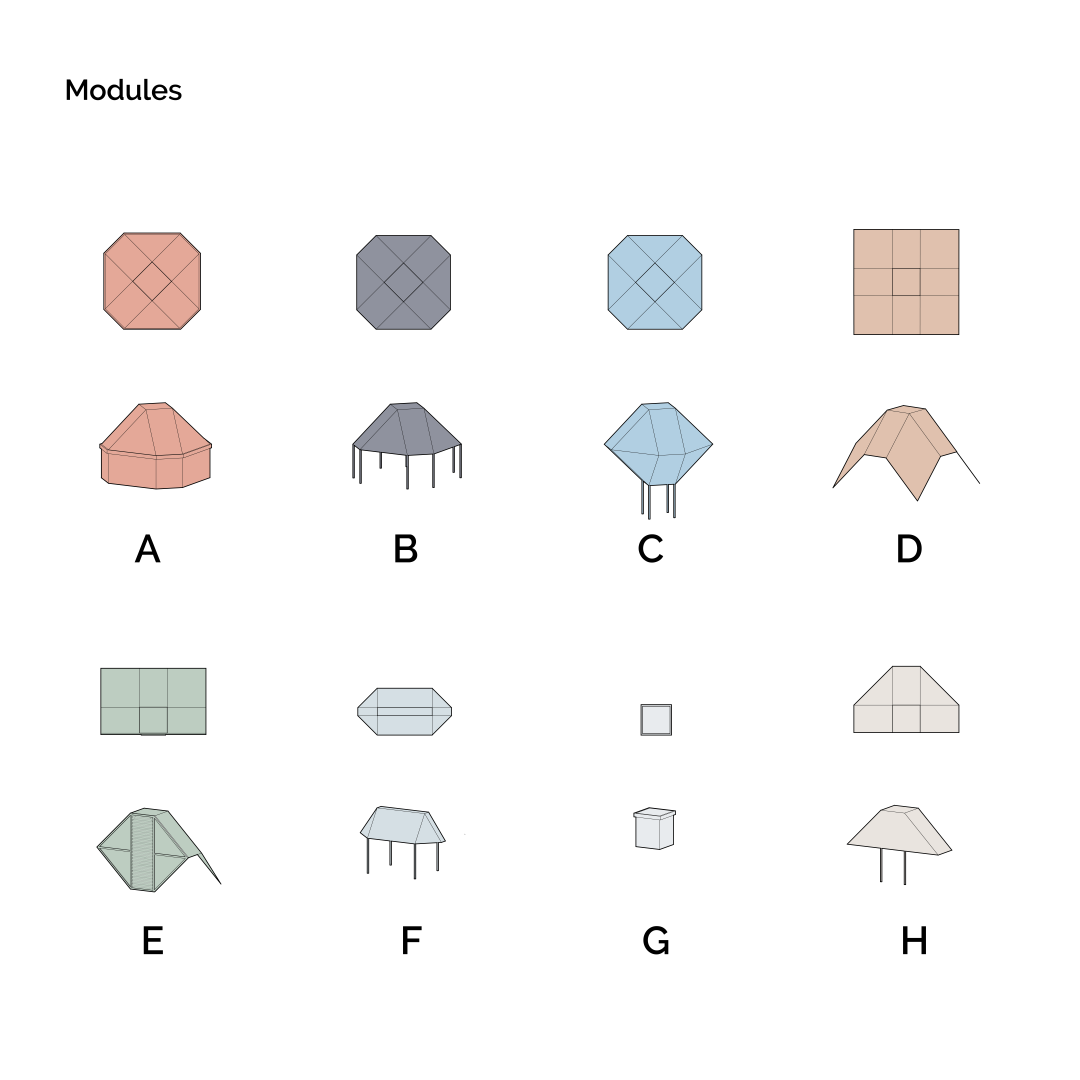

Villages

Architect Eberhard Zeidler conceived of ‘Villages’ composed of modular buildings to accommodate flexible programming at Ontario Place. Spread across three locations on the site, the Villages contained washrooms, gift shops, and various restaurants. The Village roofs were originally painted in bright colours- red, white, yellow, and turquoise. The westernmost Village is centred around a circular pit, which has housed a skating rink, roller rink, and reflecting pool at various points in time. The central Villages once hosted an Eco-learning Centre. The clustered buildings are designed to accommodate outdoor patios which became a popular attraction in Ontario Place’s early days. The Villages are not currently in use- with only the washrooms remaining open.

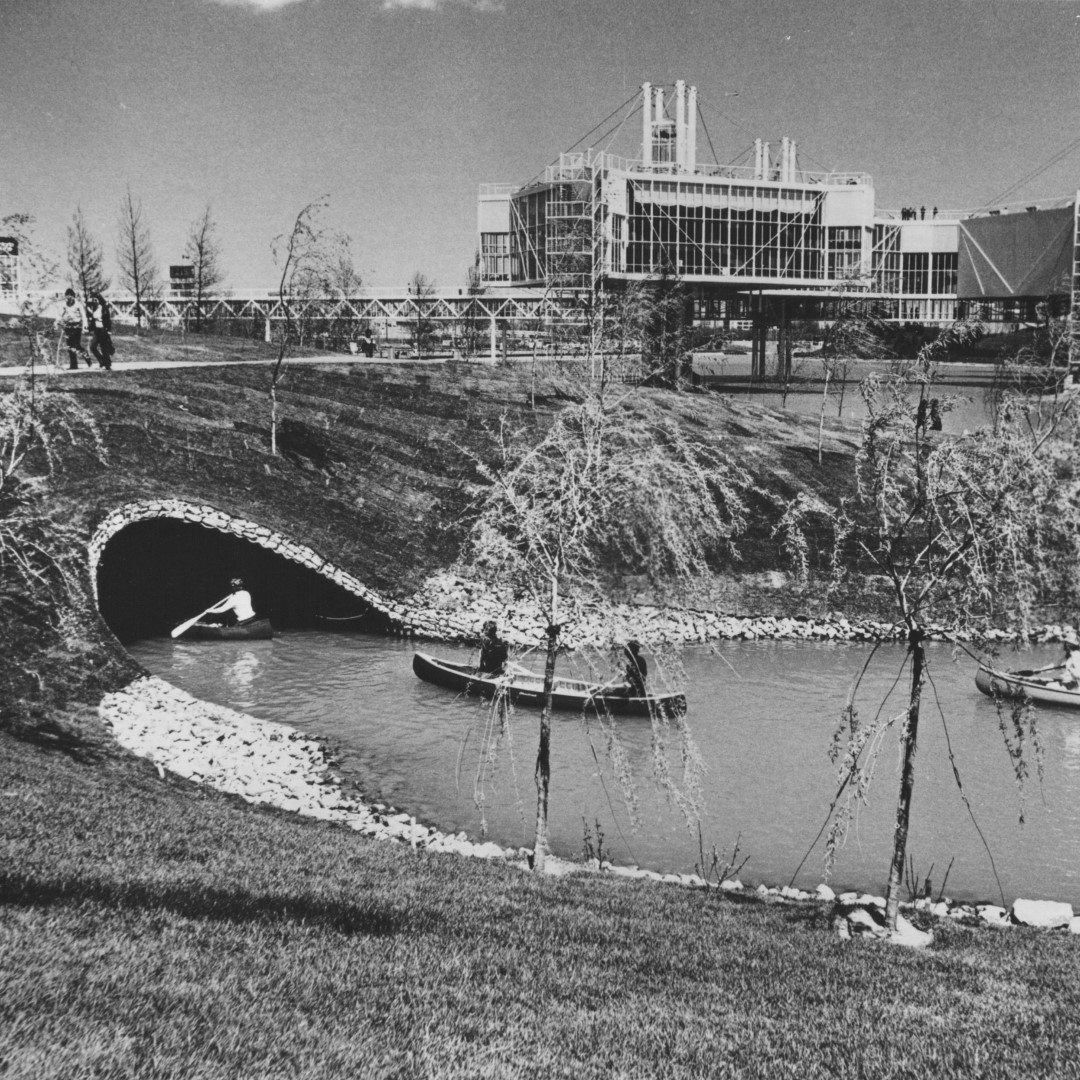

Landscape design

The masterplanning and landscape design for Ontario Place represented strong collaborative relationships between landscape architect Michael Hough and architect Eberhard Zeidler. The scale of the site, relationships between buildings, ease of circulation around the site, and surrounding wave patterns heavily shaped the landscape design. Michael Hough tested large-scale models of the site using wind tunnels to ensure comfort levels were adequate in the harsher waterfront climate. The breakwater on the southern tip of the site was formed using three sunken ships in order to maintain calm waters in the artificial lagoons. The original landscapes considered the acoustic qualities of the site, providing densely treed areas as noise buffers in order to minimize sound pollution around areas such as the Forum. Water features on site including the circular reflecting pool were designed to accommodate winter uses- transforming from pool, to roller rink, to skating rink with ease. Smaller areas such as “rocky point” on the west island were designed to allow for quiet spaces of contemplation and relaxation on the site. Native planting specifically chosen to withstand the waterfront climate was chosen to naturalize the site. To learn more about Michael Hough’s design, view his lecture here.